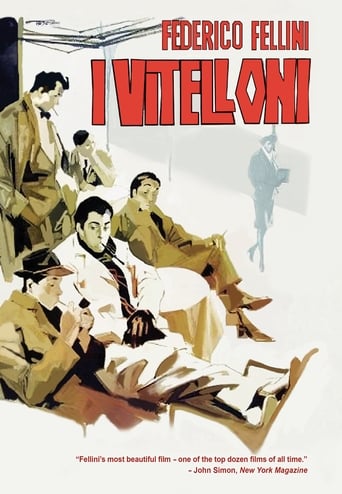

I Vitelloni (1953)

Five young men dream of success as they drift lazily through life in a small Italian village. Fausto, the group's leader, is a womanizer; Riccardo craves fame; Alberto is a hopeless dreamer; Moraldo fantasizes about life in the city; and Leopoldo is an aspiring playwright. As Fausto chases a string of women, to the horror of his pregnant wife, the other four blunder their way from one uneventful experience to the next.

Watch Trailer

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

I like the storyline of this show,it attract me so much

Very disappointing...

A great movie, one of the best of this year. There was a bit of confusion at one point in the plot, but nothing serious.

The film may be flawed, but its message is not.

You get the sense that Fellini is a reader of Flaubert, and reads him seriously; not with the common reader's fixation on Emma Bovary, nor on "charbovari" -- but with a good eye towards Emma's environment, towards Charles' viewers."I Vitelloni" explores the "boys" as Flaubert peeks at his couple. He is fond of his creations, but he does pass them judgment: we get a sense that Fellini himself is disgusted at Fausto's sleaze, but loves him for it. That is strong writing, and it shows in the final product. But it is disturbing that his fondest creation, Moraldo -- clearly the core uniting the group as revealed in the film -- is given only the screen time of any other group member. Fellini is the sort of mother the ugly child hopes for: egalitarian with her affection. This is despite Moraldo clearly vying for the place of creative "son", and the rest "nephews", perhaps with a few "twice removed"'s. It feels messy.But his strong eye for provincial life and non-provincial love unite the film in Moraldo's place, making for a wonderful experience in Fellini's personal Italy.

Set in a small suburban town in the early Fifties, I VITELLONI refers to a group of twentysomething men, all jobless, who spend their days loafing around and their nights playing pool, drinking, and roaming the streets picking up available women. They have no prospects in life; nor do they really appear willing to improve themselves. Vannucci (Leopoldo Trieste) a would-be playwright, spends much of his time pretending to work and ogling a neighboring girl.Things change when Fausto Moretti (Franco Fabrizi) has a shotgun wedding to Sandra (Eleonora Ruffo) and returns from honeymoon with a wandering eye. He makes a pass at shop-owner Rubibi's wife (Paola Borboni), and subsequently enjoys a one-night stand with a local "actress." Sandra absconds, forcing Moretti to rethink his life and make decisions.Shot in grainy black-and-white by Carlo Carlini, Otello Martelli, and Luciano Trasatti, Fellini's second feature depicts a dead-end world of cramped buildings, lonely streets and walls festooned with dog-eared posters. The group of young men adumbrate similar groups as depicted in British neo-realist films such as BILLY LIAR (1962) - testosterone-filled, insecure yet perpetually willing to show off in a world dominated by convention. To succeed in life you need to work, get married, and start a family.There are few moments to interrupt the tedium: one of these is the annual carnival, where the good burghers dress up in costumes of various hues and indulge in dancing, drinking, snogging and other revelries. Fellini communicates the desperation of the occasion with a whirling camera that circles the actors, with the music getting faster and faster ("Yes,sir, that's my baby") until it becomes a blur of jangled notes. Time passes: and we see the aftermath of the occasion, with a single trumpeter playing for an exhausted guest unwilling to go home.The film is not without its humorous elements, notably the portrayal of the fastidious Signior Rubini (Enrico Viarisio) walking self- importantly round his shop, stuffed to the brim with loudly ticking clocks and other curios. Yet the overall tone is one of sympathy for the young men, even Fausto - the forename is symbolic - whose infidelity is attributable mostly to boredom. He keeps massaging the sides of his brilliantined hair, in an attempt to render himself attractive to women; but his life is doomed to be a succession of one-night stands.The film is narrated by Moraldo, one of the group of young men (Franco Interlenghi) in tongue-in-cheek style; at the end he says that social order has been restored, but maybe temporarily. No one knows what will happen to the group in the future - save, perhaps, for Moraldo who is forced to leave the small town in search of work, as well as trying to suppress his homosexual feelings towards the young railway worker Guido (Guido Martufi). There is an overall feeling of dissatisfaction, shared by viewers and performers alike.

I vitelloni was Federico Fellini's third film and marked a turning point in his career. It ended an era and opened a new, completely different one. For those who see Fellini at his finest as a satirist I vitelloni is a masterpiece; the director's finest work. In I vitelloni social and satiric perceptions are brilliantly combined. The person gallery of the film is also brilliant and rich; it's a story of five young men who just won't grow up and leave their childhood behind. Moraldo is an outsider who spends his time day-dreaming, Fausto is the leader of the group and is in a relationship with Moraldo's sister Sandra. Leopoldo is a literature buff and a playwright without a future, Alberto is a childish character who lives on his mother's welfare, and Riccardo is a slightly over-weighted actor-singer.Federico Fellini always loved his characters and the characterization of I vitelloni is gratifying and humane. Fellini accepts his characters with their flaws but still doesn't let them get away from his moral judgments. It's truly a humane film, bitter and sad, melancholy and wistful; it's a combination of poetry and realism, dramatic and comical ingredients, which make it an integrated beautiful film.The film is very tragic, no doubt about it, but the tragicalness isn't in bottomless yearning or ultimate misery; but in precisely considered expressions and images. The 'morning' scene after the carnival is a marvelous example of Fellini's talent to depict a certain state of emotion; the tired man with a hangover, and the shadow of the mask. The beauty in this all is that the film is characterized by tragic rhythm but the tragicalness never reaches its climax - there is no storm nor thunder. It is an emotional, tragical, theme that plays through the film and by not reaching its climax the tragicalness feels even more distressing and mirthless, and is far more dramatic; in creating this atmosphere Federico Fellini truly showed his ultimate mastery.

As a Fellini film, I Vitelloni makes far less use of the curious fast-sketch scenes, surprising close-ups, proficient handling of associations between foreground and background that shaped so much of Fellini's baroque lexicon, and there are fewer of the brutes and fantastical characters that habitate his most noticed output. In places the camera-work is unusually fixed. But notwithstanding its comparatively common approach, "The Guys" takes the first absolute dive into many of Fellini's major subjective obsessions: delayed maturity in men, marriage and infidelity, the life of insular communities counter to the city, the despondent occult of bare nighttime streets, the seashore, the movies themselves. The movie hangs us on the horns of an impenetrable quandary that is the gist of Fellini's movies. That quandary takes slightly varying routes, however eventually suggests as if to branch from the strain between childhood's feeling of awe and promise, with its whirlpool of youthful reliance and collapse if the individual can't mature, and likewise the matter-of-fact and pragmatic grasp of life's obligations and setbacks, which carries its own whirlpool of likely ridicule, bitterness and degradation.This pressure identifies its most direct interpretation in the echoing images of the misuse of the incomprehensible, provocative or pure by those whose self-image or appetite for power has confused them about what is most valuable. The vitelloni are a kind of bucolic Rat Pack, living off mothers, sisters and fathers, dressing snazzily, chasing women and trifling their days away in a small seaside town supposedly patterned on Fellini's home town. Alberto Sordi and Leopoldo Trieste are excellent here, together with Franco Fabrizi, who bears a bizarre likeness to young Elvis Presley. Franco Interlenghi plays the pensive one and the only one on a quest for understanding the life they lead. Riccardo Fellini, dead ringer for his older director brother, is considerably more elusive as a character. Against their vainglory and apathy is postured the durability and wariness of the town's older men, who have seized the conventional duties of middle-class family life. Yet respectable as that may be, these solid citizens—predictable, content with their lot, stuck in choked interior settings—are barely made to appear an encouraging recourse.The closest I Vitelloni comes to any genuine representation of assurance or affirmation is the character of the station boy with whom Interlenghi passes time intermittently during his night-time roaming. I Vitelloni is replete with refined and handsomely delivered dramatic and comic moments: Sordi standing next to Fabrizi and blocking Sandra as they pose for the wedding photo; Trieste in a vainglorious rapture reading his banality-riddled play to the weathering actor Natali as the latter makes a glutton of himself and the vitelloni flirt with the female members of the actor's ensemble. Overall, Nino Rota's score strikes its own distinguishing poise between crassness and agonized reminiscence. Disinclined to endings that wrap things up too tidily, or that iron out the drama in a clear-cut fashion, despite being essentially a practical structuralist, Fellini gives us an image unfamiliar to a lot of favored filmmakers: the ending of a story shown not as a destination, instead as an adapted farewell.