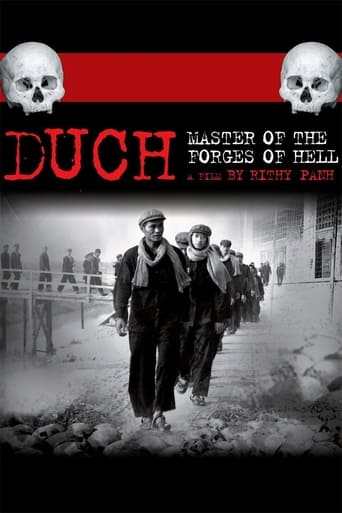

Duch, Master of the Forges of Hell (2012)

Under the Khmer Rouge regime, Kaing Guek Eav, known as Duch, directed the M13 prison for four years, before becoming the head of S21, the terrifying death machine that eliminated Khmer Rouge opponents. Some 12,280 Cambodians met their deaths here. In July 2010, Duch was the first Khmer leader to appear before an international court, which sentenced him to 35 years in prison. He appealed the sentence. While Duch waited for his new trial, Rithy Panh questioned him in depth.

Watch Trailer

Cast

Reviews

It's hard to see any effort in the film. There's no comedy to speak of, no real drama and, worst of all.

I wanted to like it more than I actually did... But much of the humor totally escaped me and I walked out only mildly impressed.

The film creates a perfect balance between action and depth of basic needs, in the midst of an infertile atmosphere.

Through painfully honest and emotional moments, the movie becomes irresistibly relatable

A correction to a previous reviewer:I was following along interested in the review for the first few paragraphs, in which the reviewer correctly noted the complexity, humanity, and even vague charisma of Duch in the film. In this Rithy Panh's work reminded me of François Bizot's book, THE GATE ("Le portail" in French), in which the author too recounts an encounter with Duch, in a different prison, before Rithy Panh met him, indeed before the KR actually took over the country. That Duch too was complex, that Duch was a good comrade in many ways, that Duch had a moral compass.However, the reviewer then mistakenly attributes the bulk of the suffering of the Cambodian people to American carpet bombing during the KR period. The reviewer even suggests that the plans of the KR may have been beneficial to Cambodians, but that they could not carry them out due to the American bombs.It is important however to understand how false this is. The Americans did indeed carpet bomb Cambodia relentlessly, but they did so earlier than the KR period, not during it. In fact the US recognized the KR government. According to Ben Kiernan, Kissinger's (and friends') punishment of the Cambodians transformed a meek and slim Communist presence into the highly oiled machine with filled ranks that was the Khmer Rouge. So blame the Americans. But blame the KR as well.One of the great tensions of this film is that Rithy Panh shows Duch in his humanity, but also the evil that humanity is capable of doing. Unfortunately the bad guys do not always look like vampires; and this makes them all the more terrifying.

I think this is the richest of Rithy Panh's three films on the Khmer Rouge that I've seen. It's the least experimental in style, we do not have the dramatic reunions and reenactments of "S21" nor the clay- figurine "performers" of "The Missing Picture", but it feels like the most challenging of the three films, the most emotionally and politically mature and complex. Perhaps this is due to the fact that its the only one of the three films to investigate in any meaningful way the ideology of the Khmer Rouge (KR), to let the KR speak for itself, in the form of one of its foremost interrogators and executioners, instead of being spoken to (S21) or spoken about with pain and loathing (Missing Picture). I found the critical receptions to the film that I've read revealingly disappointing. While all want to praise the film as historically important, they inevitably describe Duch as a portrait of either a demonic figure or an investigation into ye olde "banality of evil". The critics want to tell themselves (and us) that they (or we) could never do anything like what Duch did in the context of the KR-government, or they want to say that the context was everything- it was the situation and the ideology that was evil- and Duch himself, and others in similar circumstances, are simply empty ciphers of their time and place. I found Duch to be neither insipid nor incomprehensible as a person. An educated, sensitive man who evaluated the ideology of the KR- the most simplistic and brutal interpretation of Maoism combined with a romantic and non-Marxist ideal of rural life- and found in it a path to a better future for his country. That the realization of this ideology led Duch to commit what might be called "atrocities" does not negate his humanity, nor his capacity for self-reflection, any more than the bombings of the Muslim world reduce the Neo-Cons and Neo-Liberals to mere "monsters" or "brainwashed zombies". His remorse struck me as utterly sincere, albeit combined with an understandably caustic, even darkly bemused, attitude about humanity's capacity to "do good." At times, I felt like I was listening to an interview with Robespierre, a person who fought for modernity in a struggle so bloody that it could only have brought out all that is most primordially feral and gruesome in human nature. And here we arrive at the central problem with Panh's work, and all western (Panh has lived and worked in France all his adult life) narratives of the KR. As gruesome as their reign was, the KR attempted to govern a country in the midst of a legitimately genocidal carpet- bombing campaign by the US. Indeed, Pol Pot's vision of an agrarian utopia was inspired by seeing forest-dwelling peasants who were relatively unscathed by the air assaults. That trying to govern a society under such attack inspired paranoia and brutality on the part of the leadership is far from incomprehensible. Panh's hatred of the KR is also understandable. As detailed in "Missing Picture" he watched his family starve to death in a KR work-farm. But in that film he treats the lack of food as an act of sheer cruelty on the part of the government, rather than a simple fact of scarcity caused in no small part by the dropping bombs. But Panh is, like everyone, shaped by his experiences. He describes himself in "Missing Picture" before the KR came to power, sitting with his well-off family in movie palaces watching as "movie stars sang, as if only for me."

I saw this film as part of the Rotterdam Film Festival 2012, an impressive documentary about the Red Khmer (Khmer Rouge) in the years between 1975 and 1979. It gives us heavy food for thought, especially about shifting off responsibilities and the willing-less following of orders from above.Rather early in the monologue held by our main character, called Duch for short, he confronts us with a few loaded sentences. For example: "It is better to kill one innocent man than to let a guilty one go", contradicting any judicial process as we know it. He also reads several quotes from Marx and Mao about (freely translated) sanitizing the population to eventually get a clean working class. He brought these book theories into practice to its full extent. Take for example that he recalls having not interfered after his grammar school teacher was captured and interrogated; otherwise he might have been accused of "individualism", that being nearly the worst you could say about someone.He denies to have tortured or killed anyone, albeit he admits a few exceptions in the line of duty (he taught "interrogation techniques" as an officer). Another core statement is that everyone in the camps under his command is going to die but never too soon, in other words not until they got what they want.His monologue is mixed with witness reports, partly contradicting Duch's statements, and partly underlining the horrible things that Duch talks about in very abstract terms. The latter is visualized by documents that Duch shows, with annotations in his handwriting, explicitly demonstrating that he ordered execution or "further interrogation". He also states to have never witnessed torture, but left that in the hands of subordinates. He only saw the reports, passed those on to central government when appropriate, or returned them to subordinates for further "processing", the latter augmented with instructions written in the margins. On the outside it looks not different from what we see in any bureaucratic organization, like a bank, where paper replaces things in the real world that the bureau worker never sees.All in all, a memorable witness statement from both sides. It surpasses any Amnesty International report, in demonstrating how such cold killing machines can exist and how they operate. This topic is not tied to Cambodia, but applies world wide, and it already existed many centuries ago. It shows the underlying mechanisms, and how torturers and executioners are able to cope with this reality. Apparently, what they merely do it putting it on a higher level of abstraction. Or they categorize their victims as "bad" people (reasons for marking them bad depends on political context), who deserve this harsh treatment and eventually elimination.