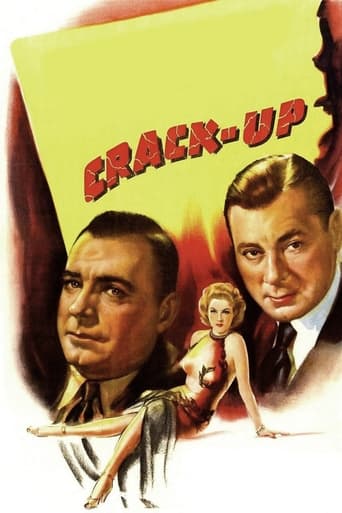

Crack-Up (1946)

Art curator George Steele experiences a train wreck...which never happened. Is he cracking up, or the victim of a plot?

Watch Trailer

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

Let's be realistic.

I wanted to but couldn't!

It’s sentimental, ridiculously long and only occasionally funny

Blistering performances.

In no other American film noir does art and the museum play such an important role. The main character is an art expert, and significant themes include Old Master paintings, forgeries, and even the use of x-ray technology. Granted, Fritz Lang's "Scarlet Street" (1945) involves the entanglements of an artist (Edward G. Robinson, an important real-life art collector) and mistaken identities. But in Crack-Up the institutional art world––museums, curators, and collectors—are integral to the plot. This film is also notable for representing a museum professional as a tough, noir male lead. His name is, fittingly, "Steele" (Pat O'Brien). When he powerfully hits an arcade punching bag, one character observes, "Not bad for an art critic." O'Brien's soft-spoken intensity and mature demeanor are perfect here. Similarly, the museum is shown here as a foreboding and noir-ish place, an unusual treatment; recall the bright, Technicolor San Francisco Legion of Honor in Hitchcock's "Vertigo." In one scene in "Crack-Up," the shadow of an ancient figural sculpture looms like a spider over the guilty museum director. The opening of the film, set to the shrieking tones of Leigh Harline's discordant score, shows a train speeding right at the viewer. In rapid succession we see Steele's crazed face, then his foot kicking through the glass door of a museum. Wrestling with a policeman, the pair jostles an ancient classical statue—a torso, surreal in its own way––which nearly crushes Steele as it shatters on the ground. In the background we see the well-known "Farnese Hercules" (216 AD) in a hall of classical statuary. The most telling scene for art in America at this time occurs early on, when Steele is shown lecturing in the museum's galleries. He wonders why art gives American viewers "an inferiority complex," and that "face to face with a painting we shuffle our feet and apologize." He continues: "Why apologize? If knowing what you like is a good enough way to pick out a wife, or a house, or a pair of shoes, what's wrong in applying the same rule to painting?" He then shows the crowd Jean-François Millet's "The Angelus" (1859), a hugely popular nineteenth-century painting of two peasants pausing from their fieldwork to pray. The audience makes reverential noises, but gasps in horror when he pulls back the cloth over a contemporary Surrealist painting. The picture (uncredited) resembles Salvador Dalí's "Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War)" (1936). Steele calls it "nonsense" and equates modern painters with forgers. Both are dangerous, he claims, as "good technicians with nothing to say." In the 1940s Americans were still bewildered by European modernist painting including Cubism, Constructivism, Dadaism, and Surrealism. Intriguingly, at this moment, the American Abstract Expressionists were just picking up steam. A heckler (the great Shimen Ruskin) suddenly challenges Steele. He vociferously defends modernism, distinctly foreign in his thick accent, Hitler moustache, and floppy tie. After he is physically removed, accompanied by cheers from the crowd, Steele invites his audience to next week's lecture on modern art, quipping, "Surrealists will be searched for weapons at the door." His populism contrasts with the misanthropic collector Lowell (Ray Collins), who sneers, "Museums have a way of wasting great art on dolts, who can't differentiate between trash and these masterpieces ." A wide appreciation for art—and by extension for democratic American values––is also at odds with the snobbery of the art dealer Reynolds (Dean Harens), Steele's romantic rival for Terry (Claire Trevor). Steele is soon fired from his position for addressing the perceptions of the masses. He wanted to breathe a little life into the staid museum, he says, and make art accessible for everyone. He goes too far, however, when he invites the audience to use radiography to examine Old Master paintings, which threatens to expose the art villains' scheme. The train crash can be seen as a metaphor for the war itself as well as the trauma Steele and movie viewers have suffered. Perhaps it too was a false nightmare concocted by the rich and powerful. The veteran Steele and his audience need to reengage with an understandable post- war world. His longing for truth extends to his career expertise in authenticating art, and plays out in his subsequent hunt for the authentic museum masterpieces. It also helps explain his antagonism to modern art, which doesn't resemble everyday reality. (Ironically, Surrealism aptly describes Steele's own hallucinatory experiences and the world in which he now finds himself.) And his detailed attempt to recreate what happened on the train––in essence a "forgery"-- parallels what he'd later do in the museum's conservation lab to distinguish the real Dürer from the fake one. In a scene that must have seemed very high-tech to movie audiences of the time, Steele examines pictures in the museum's lab. Comparing the original to a forgery, he observes, "It's physically impossible for two men to paint exactly the same." This also articulates the plight of the highly individualistic noir hero, who must endure his own solitary journey to arrive at an exonerating truth and justice. Steele's sleuthing recalls what the actual WWII "Monuments Men" were doing only two years before in Europe, tracking down world masterpieces and foiling the Nazi's plans for hoarding and selling them. But now the art villains are in America, and they're dealers, wealthy collectors, and museum officials. Like the Nazis, they would deny citizen museum-goers the authentic masterpieces of western culture. Overall, this film dramatizes nationalistic debates about art in a new post-war world while it attempts to engage the surreal trauma of WWII––still the deadliest conflict in human history.

Pat O'Brien was wonderful supporting actor. Having him as your lead was kind of unusual -- not to mention having him play an expert in art. He does a great job, though, as does the whole cast. Claire Trevor, in a way, is the only major name actor. Ray Collins is good but maybe not up to the pivotal role he plays. In a small part, Mary Ware is very effective.Charlie Chan movies occasionally involved art thefts or forgeries. Of course, there is the black bird in "The Maltese Falcon." But generally, this is an unusual setting for a film noir, which this definitely is.It's tense but maybe not so tense as it might be. I like Hitchcock but do not worship at his feet. Whoever, had he directed this, it could have been a tight, thrilling picture. He'd have story-boarded it all before filming and we'd have been on the edge of our seats as ti played out.He didn't, of course, and it's still a really good movie. It's noir with a highbrow twist, just as "Red Light" -- which I haven't seen in 15 years and wish would turn up -- is noir with a religious setting.

In Crack-Up the idea is to make art expert Pat O'Brien think he's done just that. O'Brien wants to bring in some x-ray equipment to show how art forgeries can be done to stimulate interest in his lectures.Of course when you've got that going on at the museum, there's going to be someone who doesn't anyone snooping around. So O'Brien is framed with an elaborately concocted train wreck. Of course the train wreck never happened and people start thinking Pat has cracked up.The only one who believes him is girl friend Claire Trevor and between the two of them, they've got quite a task before them. To convince everyone including police detective Wallace Ford that O'Brien is still playing with a full deck and find out just why someone wants everyone to think there's a suit missing from that selfsame deck.Crack-Up is a good noir thriller from a studio which turned out quite a few of them in post World War II Hollywood. RKO always operated on a shoestring and the nice thing about noir films is that you didn't need a big budget. A good script and solid acting is usually what put over a noir.Herbert Marshall lends some British authority as a man from Scotland Yard who acts very mysteriously indeed. For those who like the noir genre, they will not be disappointed.

The title of Irving Reis' Crack-Up sums up two elements of its plot: the wreck of a train carrying Pat O'Brien and the psychotic episode he throws in its aftermath. He gives lectures at a New York museum, demystifying art for the masses, who obligingly moan reverently at Monet but hoot derisively at Dali. When a phone call (sick mother) summons him upstate, he boards a train on which he freezes like a deer in the headlamp of a renegade engine hurtling straight at him. Oddly, he survives, but upon his return hurls a fire extinguisher through the gallery doors, assaults a policeman, and babbles incoherently about the accident. Trouble is, Mom's in fine fettle, and there was no crash.The movie joins him in sorting out the dramatic turns his life has taken. Helping him is Claire Trevor, a fixture in Manhattan art-snob circles. Herbert Marshall purports to help, too, but he keeps his cards close to his vest. Quite candidly not much help are the museum's board and its snooty benefactors, among them Ray Collins, who were never keen about the democratic spirit O'Brien breathed into their mausoleum and use his erratic behavior to halt his series of light-hearted talks. The police, too, have a stake; O'Brien did, after all, throw that punch....One of the felicities of Crack-Up is that it takes its canvases seriously, putting them at the core of the story. (A similar respect for art, music and theater, and for audiences assumed to have some acquaintance with them, routinely elevated films of the 1940s; times, plainly, have changed.) Of course monetary rather than esthetic value drives the villains here, as O'Brien slowly uncovers an international art scam, which is why he was derailed in the first place.The train crash itself a very scary sequence, brilliantly handled by Reis emerges, in the final wrapping-up, as the weakest point of the movie, a baroque twist too far-fetched to convince. Because of this contrivance, the movie cleaves to the over-plotted mysteries of the 1930s and early 1940s rather than to the emergent noir cycle that, in its look and many of its devices, it otherwise resembles. But then there's the always toothsome Claire Trevor, whose ensembles take inspiration from the uniforms of the just-won war; festooned in military braid and berets, she tilts the scales towards noir. Either way, Crack-Up offers some suspenseful fun spiked with a surprising note of sophistication.