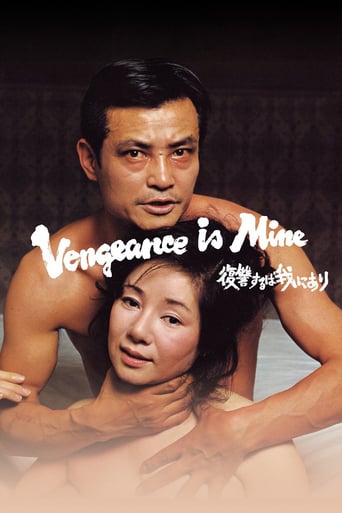

Vengeance Is Mine (1979)

A thief, a murderer, and a charming lady-killer, Iwao Enokizu is on the run from the police.

Watch Trailer

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

So much average

Powerful

An Exercise In Nonsense

It's easily one of the freshest, sharpest and most enjoyable films of this year.

In late 1963 a serial killer and conman Akira Nishiguchi gained nationwide attention in Japan by murdering five people, several of them while on the run from the police. In the late 1970s a book based on his life inspired the master director Shôhei Imamura to use his story as the basis for a cold crime film titled Vengeance Is Mine. The film starts with the capture of the killer Iwao Enokizu (Ken Ogata) and advances non-chronologically, depicting the detectives interviewing his family and former lovers and how Enokizu first came to know them. Particularly the muted relationship of Iwao's wife Kazuko (Mitsuko Baisho) and his Catholic father Shizuo (Rentarô Mikuni) is paid attention to, so is his stay at a brothel-like inn managed by Haru Asano (Mayumi Ogawa) and her ex-con mother Hisano (Nijiko Kiyokawa). The scenes ranging from Enokizu's childhood to his time in death row cast light on what kind of man he is, but avoid serving easy, clear-cut explanations of his inner motives.Imamura has taken an unspectacular, down-to-earth approach to his enigmatic subject. Some techniques, such as identifying the victims' names and causes of death by subtitles, are not far from the style of documentaries. While some of Enokizu's killings take place off-screen, the depicted murder scenes are not softened by turning the camera away or fading to black, making especially the sexual violence hard to watch for sensitive viewers. Still, Vengeance Is Mine is more of a character study than a crime thriller, as in the latter parts of the film the detectives' role is diminished and the focus turned to Enokizu. He is portrayed as having been belligerent and self-confident from young age, soon blossoming into a full-blown psychopath to whom other people's feelings are of little concern, as exemplified by his cruel psychological treatment of his family. Even if Iwao's basic nature is inherent, it could be possible that the suppressed atmosphere in his parents' home has affected the way he turned out: the deeply Christian father sparks Iwao's hatred for weakness and humility, prompting him to openly mock the lack of action from the family's part when feelings develop between Kazuko and Shizuo.Besides his twisted relationship with his family, another defining element in the film is Enokizu's stay at the inn with Haru, a mistreated woman who has to look after her unreliable mother. Imamura's portrayal of Haru is highly forlorn; to her Iwao's presence represents a possibility of freedom from her gloomy life, even when his past is no longer a secret to her. It is also during this time when the stress of being a fugitive is starting to take its toll on Enokizu; he turns from a self-confident fraudster to a more serene and openly menacing figure, an interesting change as we, the audience, already know him as cocky and carefree from the first scene that has yet to happen in the story's timeline.The very dark lighting in the interior scenes and the slow-paced, detached storytelling will alienate those expecting a suspenseful serial killer thriller, but as a flat-out drama Vengeance Is Mine provides a fascinating trip into the world of the suave killer. Ken Ogata handles the lead role with natural charm, effortlessly fitting in the various roles Enokizu assumes over the course of the film. Rentarô Mikuni also makes a great counterforce to him as the guilt-ridden father, but especially the unlucky women Haru and Hisano are powerfully brought to life by Ogawa and Kiyokawa. The visuals are not as aesthetically striking as in Imamura's earlier masterpiece Unholy Desire (1964), but the mood is so heavily tied to the reality of Japanese society in the 1960s and 70s that the depressing mundanity of the surroundings is never out of place. The only moment rising above the strictly realistic atmosphere would be the very final scene on the top of a mountain: Enokizu's spirit will remain lingering in the lives of those around him. All in all, Vengeance is Mine should not be ignored by any enthusiast of crime cinema, but admirers of slow-burning character dramas are probably the ones to find it the most rewarding.

Iwao Enokizu, his life of crime and those he came in contact with(..many killed by his hands)along the way. The film elaborates Iwao's disconnect with his Catholic father and unhappy wife Kazuko, along with his budding romance to a sad and mistreated "kept woman" who runs an inn which services male clientèle with call girls from another location. Iwao never spends time too long in one place and travels throughout Japan donning different aliases, wearing various disguises(..professor, PR assistant, lawyer), always swindling people who fall for his cunning con-games. It seems that he kills those who treat him kindly, give him a place to stay, and show affection towards him, when, in actuality, Iwao would rather murder his father and wife. The film establishes the lust harboured between Iwao's father and Kazuko, not embracing each other(..she makes efforts, but he resists due to his religious ways)due to the ailing mother who knows how they feel about each other.Iwao's contempt for his father went back to childhood when pops surrendered boats to the military empire, and he would rebel his wishes throughout the rest of his life. Director Shohei Imamura doesn't exactly follow Iwao's life in direct order as is often seen regarding the history of someone, going back and forth(..at times retreating back to the jail cell as Iwao's recollects what brought him to the confession room, awaiting his future trip to the gallows), to the past and to the search for him. That's something, Imamura never fails to remind the viewer of, the manhunt/search for Iwao. It's quite exhaustive and covers a lot of ground.You often notice how those that come in contact with Iwao mention fate that they crossed paths with him, quite a morbid chill would come over me because these innocent people were doomed and just didn't know it. And, the murders at Iwao's hands are savage..Imamura shows Iwao pummel a very decent man with a hammer across the head, before viciously stabbing him, also attacking the victim's co-worker with a purchased knife not long after. The most unsettling was perhaps his strangling of a female victim, actually allowing her to catch a breath before finishing the poor woman off.. cleaning urine from her legs afterward. Even those murdered off-camera(..a retired attorney who lived in isolation, offering Iwao a place to stay, another he would suffocate with a rope, removing her ring to pawn for money)leave a lasting impression. He does so without much compassion, not seeming to show any remorse or guilt for committing his crimes, removing their money to keep him financed on his adventures. Interesting conclusion(..besides his father and wife's attempts to toss his bones with them freezing in the sky:even in death they could not rid themselves of Iwao's presence)where father and son meet one last time, painfully both open to each other regarding their contempt and disappointment for one another..I think Iwao, once and for all, lets us have a peak into his guarded psyche when he informs pops that he could never run far enough to escape his reach. Imamura, interestingly, seems to hold a rather scathing view of Catholicism and it's hypocrisy, using Iwao's father as a firm example of the nearly impossible resistance of desire, no matter if he touches Kazuko or not. Imamura returns to them time and again showing their discomfort around each other due to their desire and those who blatantly bring it to light. The place Iwao returns to(..his other "family")is the Asano inn where Haru provides a place for men to "let their hair" down, to gamble and screw in peace. Haru's "sugar daddy" comes around at times to check up on her(..or to flaunt his newest floozy)and he has her mom peeping around at night on customers(..his "eyes" when he isn't around). Haru also services him(..one disturbing scene shows him rape her with mama not interfering on her behalf, displaying just how desperate they were for the home he provides). Haru, despite her status in life, appeals to Iwao and this relationship(..also highlighting the rocky feelings between Iwao and Haru's mama)is also elaborated to great detail.One thing's for sure, Imamura's film openly displays sex and violence, the unpleasantness of both vividly brought to our attention over the lengthly running time. Ken Ogata convinces as the criminal, conveying a tortured soul, who seems to, most of the time, cloak those feelings within a cold demeanor, the beast only unleashed when confronting his father and wife. Women are often not treated with the utmost respect or honor, almost all damaged in some way.

The title leaves an assumed puzzle that is never solved. I mean, vengeance for what? This characterization of a savage serial killer implies a cold-blooded compulsion lacking incentive, stimulus, reason or distress. Different from other socially anthropological movies in the true crime genus, it has no Freudian commentary for everything and shows us straight depravity, heartless and inaccessible. A few scenes from the killer's boyhood feel almost like sardonic breakdowns of how any explanation would be implausible. We are made conscious how much we yearn for such stories to define their vileness.This richly visual artistic examination unravels unsuspectingly. We see a murderous sociopath who kills two money lenders in a gory opening scene. Then flashbacks are unified with his escape through Japan as his hopeless upbringing and the buildup of his sinister, sociopathic way are interpreted. Monstrous and libidinously barbaric, his agitation boils during an earlier stay in prison as he imagines his wife is having sex with his father. When on the run from the police, his bizarre sexual life and violent nature are yet unraveled in a succession of consuming action. He is played by the powerful actor Ken Ogata, who uses two major demonstrative modes, fury and detachment. Sometimes he can be eloquent and even charismatic, but merely to the advantage of sex, theft or murder. His face camouflages perhaps nothing.At the very beginning, we see Ogata in the back of a police car, after his arrest. He has been the case of a nationwide pursuit for months, his photograph everywhere. Ogata sings tunes, contemplates the day of his hanging, declines to accommodate the questions of the police. His view is that committed the crimes, his death is justified, all is as it should be. The first murder, the two lenders, is committed with lots of struggle, the victim fighting back like crazy, our killer nearly overpowered, blood everywhere. He leads the second man to the same site, kills him too, washes up and changes, composed and dispassionate.Imamura's absorbingly stylized murder epic will show all of his murders, but only that elaborately just one other time. Imamura knows that when you introduce violence, it can later keep its effect merely with the summoning its thought. With another murder, he makes friends, then murders him, shuts him into a cupboard in the victim's own apartment and then explodes with rage when he can't find the can opener. He wasn't enraged by his victim, but the can opener makes him desperate because he can't kill it.There are subplots concerning two families, Ogata's and another a mother and daughter in whose lodge he lies low, involving the depravity of both sets of horrifying parents and the demoralization of the children. Ogata's marriage is comatose, his mother is hospitalized, and there has long been an intense gravitation between his wife and his father. While they graze sex during a hot bath, they counteract because of their obsessive Catholic values which somehow do not defy the father to persuade a friend to have sex with her. She opposes, until the man tells her he has the permission of her father-in-law. The lodge where our killer hides is run basically as a whorehouse, and the mother is an ex-convict, released after a sentence for murder. The daughter schedules call girls for the lodgers, and is herself the mistress of a businessman who pays the rent. The two women are decidedly deadpan about this set-up, and it leads to some odd dialogue.This extensive, dubious and apparently true story amasses formidable energy. Everyday human values are deducted from all the major characters, and that is demonstrated above all in two scenes that disturbed me far beyond any of Ogata's deeds. Once when it is suggested that his father and wife torture and kill a dog for biting her, and again when the businessman rapes the crying, begging innkeeping daughter, with Ogata and the mother in the next room. Ogata seems impassive, rivets on a dripping faucet, tightens it and then at last grabs a knife, but the mother stops him. Having been filled with explosive tension throughout the scene, I was baffled by this frustrating move, but then I realized she does not want to lose the man's rent money.What is most alarming about Ogata's character is that he has no conscience at all about his murders. It is just his nature to kill. Does he have such hatred for life that he is killing unoffending passers-by just to be hanged by the state? Surely the innkeeper's daughter hasn't recognized any inference that he loves, likes her or even regards that she's alive. Perhaps she's also like an insect. I mean, he never says one congenial sentence towards her, actually communicating largely in laconic aphorisms.As a stylist, Imamura is a virtuoso, his camera often a little above eye level, diminishing his characters, maybe manifesting them as segmented, already deconstructed samples. In other shots, he shoots from low angles with deep-focus environments, as in the scene where Ogata seethes in the kitchen while the daughter is raped, when the dripping faucet is framed and lit to poke at his attention. Throughout the murders, his camera restrains its breadth, not moving, at one point shooting straight down. He does not delight in shock cuts or sudden whip-pans. His camera beholds impartially. It's rare to find movies that really deflect your thinking and make you suffer to fulfillment. This film is a definite shock, and enlightening when it comes to the judgment and expectations of characters.

Ambiguously-titled and multi-faceted, this is probably the best film I've watched so far from the director (who, coincidentally, died just a couple of days prior to my first viewing of it!).This is far more than merely the case history of a criminal; indeed, despite being based on true events, the film still emerges as typical Imamura in its revolving around a family unit, the multiple characters, its emphasis on sex and suggestion of incest, the brothel milieu and the elliptical narrative! VENGEANCE IS MINE also marked the director's return to feature film-making, having spent the previous 11 years shooting documentaries subsequent to the failure of his 1968 epic THE PROFOUND DESIRE OF THE GODS (1968; which I had recorded some time ago off Italian TV, but the tape unfortunately was scrambled!).As always, the entire cast delivers excellent performances and many of them were duly honored for their work here. The film is long but never boring, indeed fascinating in its methodical, deliberately-paced approach and especially the clinical detail of the chilling crimes (though some of these actually occur off-screen). Imamura inserts several subtle instances of surrealism (most notably a series of freeze-frames at the conclusion) without them appearing incongruous in the face of the realism that is otherwise demonstrated.Alex Cox's video introduction on the MoC/Eureka SE DVD is brief but insightful, but Tony Rayns' full-length Audio Commentary and the accompanying 36-page booklet are customarily comprehensive.