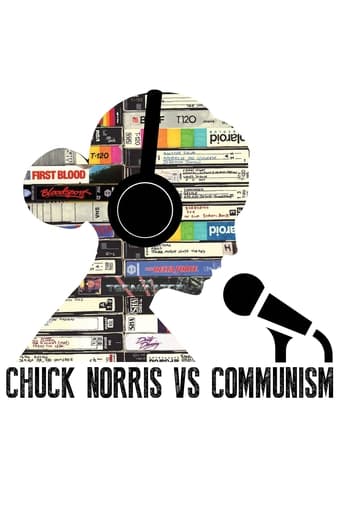

Chuck Norris vs Communism (2015)

In late eighties, in Ceausescu's Romania, a black market VHS bootlegger and a courageous female translator brought the magic of Western films to the Romanian people and sowed the seeds of a revolution.

Watch Trailer

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

Beautiful, moving film.

Absolutely Brilliant!

Story: It's very simple but honestly that is fine.

Exactly the movie you think it is, but not the movie you want it to be.

I never knew a historical document about a conflict- book, film, whatever, that was perfectly balanced, but I believe that this film is better than many on this score. I urge you to listen to the podcast of Irina Nistor's interview on the public radio program Fresh Air, which includes important details left out of the film and also recounts what happened immediately after the incidents in the film. I liked the music and the lighting, but they seemed derivative of the documentary The Thin Blue Line, which is also excellent and which I commend to your attention.

"Chuck Norris vs. Communism" is a provocative title for a movie about cultural provocation. This documentary, combining interviews with shadowy reenactments, explores the underground video culture of Romania in the 1980s when the government of Nicolae Ceaucescu, controlled everything in Romanian society. People could not travel to other countries and television "progressed" from two available channels down to one. Then, in the mid-1980s, people began smuggling videotapes and VCRs into Romania. According to Constantin Fugasin and Emilian Urse, people had a hunger to see something different from their bleak lives, and Western films brought them more than the action of "Rambo" and "Missing in Action" or the sexiness of "Dirty Dancing." They also brought the chance to see other countries as well as the clothes and music that were banned in Romania.Black market videos were distributed to more than 10,000 VCRs, which were viewed in crowded living rooms. VCRs cost as much as a house and the smuggled video tapes were ridiculously expensive; so, unsurprisingly, exhibitors charged a fee to those who came to watch videos in their apartments.The videos were copied from copies and were copied over and over until the quality was very poor. Also, the secret police would sporadically raid these home theaters and confiscate the VCRs and the tapes from exhibitors like Simion Barbu, who is interviewed in the documentary. Barbu notes that he could have been sent to prison, but he was not in his case. He recalls asking the police whether they had a warrant. "Do you believe this guy?" said one of the police. "We'll get a warrant, and then we'll come back in half an hour and tear your home apart."One wonders whether Barbu was emboldened to ask for a warrant based on the American movies he had seen. The interviewees, especially those who were children in that period, all attest that watching heroic films made them think that they could be heroes, too. It was an attitude that could get someone hurt, but it was an attitude that spread to millions of video viewers, and the government could not kill all of them.At the heart of the film are three remarkable people. One of them was Teodor Zamfir, a savvy businessman who cornered the market in bootlegged videos. He eventually had to bribe government officials— including the son of Nicolae Ceaucescu—by giving them video tapes.But Zamfir's monopoly was not only based on his access to videos. He also had the dubbing equipment to bring English language films to a Romanian audience, which brings us to his fortuitous hiring of Irina Nistor, a government worker who spoke fluent English and turned out to have a knack not only for translating but performing the dialogue in the movies she dubbed. One of the most touching aspects of the documentary is how all of the interviewees fondly recall her voice, speaking for both male and female characters. No one knew her name or what she looked like, but she was a star. She estimates that she dubbed over 3,000 videos.Viewers were amused by her quirks. She would never translate foul language. If Hollywood actors said, "F___ you," she would inevitably translate it as "Get lost." One of the interviewees swears that she once translated "I love you, I want to f___ you" as "I love, get lost."In an incident that demonstrates the schizophrenic attitude of the government, she was called into the office of an official who berated her for using the word "God" in dubbing the movie "Jesus of Nazareth." "You should have said, 'the one above'," she was told. So officials not only knew that Nistor was the voice of the illegal video industry, but they were watching these videos themselves."There were other voices, too," says one interviewee, "and I didn't like him. To me he was the fake version. She was the original."The male voice that dubbed some of the videos belonged to Mircea Cojocaru. (Rather than have Nistor do the female voices and Cojocaru do the male ones, they compartmentalized the dubbing so the two voice artists could have plausible deniability in case they were ever forced to testify against each other.) He may not have been as popular as Nistor, but he saved Zamfir and the bootleg industry on one fateful night when the studio was raided. Zamfir stood up to the secret police, and one of them put a gun to his head. At that moment, Cojocaru broke his cover and revealed that he was an undercover agent all along, assigned to spy on Zamfir. The police withdrew, but rather than arrest Zamfir, Cojocaru continued dubbing videos. This is how schizophrenic Romanian society had become, with everyone watching everyone and all informing on each other, but it no longer prevented dissent. People felt intimidated, but more and more they overcame it and acted boldly. In 1989, people finally did pour into the streets, and Ceaucescu was overthrown. Why did the dictatorship allow so much subversion? Fugasin and Urse think the government did not know how widespread the videos were and wanted to believe that only government officials and maybe a few regular citizens were viewing them. They thought a raid now and then would keep a lid on the problem. They never dared to contemplate the enormity of it.Zamfir, himself, believes that the government thought that even if it was a widespread phenomenon, people watching foreign videos was "insignificant" and "trivial." They did not understand how important the videos were to people who had been starved for a glimpse of a different world or how the videos stimulated inner hope and strength that viewers came to share.

I read a review here on IMDb by a Romanian and am am sure this person would be a much better judge of the central theme of this documentary. They felt that "Chuck Norris Vs. Communism" overstated its position that the illegal import of American 1980s videotapes into Romania served to introduce Western ideas into this communist dictatorship and this led to the fall of the government in 1989. While I agree this reviewer that this was overstated a bit, it surely had some impact on changing attitudes. However, the context of the time also must have had a lot to do with it as well...something never even mentioned in the film. In other words, communist bloc nations were throwing out their governments by refusing to work or do anything until their leaders resigned...and Romania was just part of that wave. So, I agree with tributarystu...but it's still well worth seeing.The film uses interviews and recreations to explain how Romanians smuggled in American films. Additionally, mostly one interpreter dubbed the movies (doing ALL the voices) and there was a cottage industry that was illegal but overlooked by various government officials. After all, they liked watching the films and there was some sort of payoff going on as well. It's all interesting and worth seeing...if a tad overstated.

In spite of being born towards the end of the 80s, I recall several "Margareta Nistor movies", her trademark dubbing scarring my youth alongside the zombies of Return of the Living Dead. It's funny, particularly because her often inflection-less voice made the humor of the movie much harder to understand at the time. Then again, maybe that had more to do with me being less than a decade old myself and thinking I might be immune to the undead.At its heart, CNvsC is a film about the passion of movies. During communist Romania, in the especially dire last ten years of Ceausescu's reign, an illicit business venture involving the dubbing, copying and distributing of Western cinema spawned and spread like wildfire in what became a cultural landmark of the times. Rocky, Missing in Action, Once Upon a Time in America, Bloodsport, Dirty Dancing are just some of the many movies featured. Using current day interviews with both the protagonists of the movement (foremost Mrs. Nistor as the "localization" specialist, Mr. Zamfir as the ambivalent VHS peddler) and Romanian personalities, as well as laborious reenactments of key events, director Calugareanu portrays the dichotomous fear/love relationship of treading the anti-establishment line. At its best, the film is humorous and playful, insightful with a dark edge in exploring the oppressive machinations behind the scenes. While hyperbolizing, it sets itself up as a thoroughly enjoyable ode to a movement that played a part in empowering the Romanian people. But the causation is forced and based on weak evidence. The urge to make such a powerful claim and even the attempts of dramatizing certain events play against what CNvsC is really strong at: highlighting the cultural impact and the adventurous affairs surrounding a seemingly banal act of translation. What it fails to do is look beyond the immediate effects of the whole process and the romance of movies as an escape from the everyday. Questions like how the exposure to a fairly homogeneous body of films affected Romanians' world-view, especially given that most of the films were not quite paragons of Western film-making, is not tackled. Nor is the matter of how the practice of what essentially is piracy contributed to a certain cultural acceptance of digital duplication in decades to come, as seen across the Eastern block. At the screening, Nistor mentioned that she had met her counter-parts from Estonia or Russia, who were different to her only in that they were all men. So, while on the one hand the documentary works as a look into a pretty special phenomenon, it is frustrating that it avoids going deeper into either the social ramifications, or further exploring the more personal experiences of the likes of Mrs. Nistor to let the local interpretations take hold of an otherwise too descriptive approach - aimed to a more universal audience, with little knowledge of Romanian oddities.