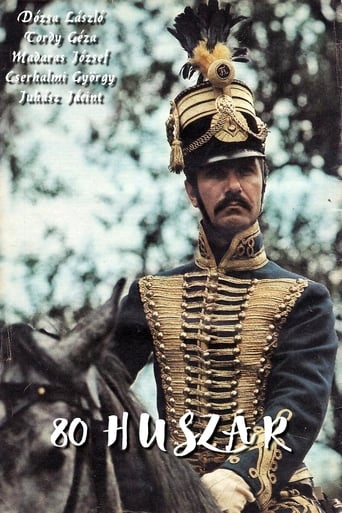

The Round-Up (1966)

After the failure of the Kossuth's revolution of 1848, people suspected of supporting the revolution are sent to prison camps. Years later, partisans led by outlaw Sándor Rózsa still run rampant. Although the authorities do not know the identities of the partisans, they round up suspects and try to root them out by any means necessary.

Watch Trailer

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

The Worst Film Ever

Absolutely Brilliant!

The film creates a perfect balance between action and depth of basic needs, in the midst of an infertile atmosphere.

Great story, amazing characters, superb action, enthralling cinematography. Yes, this is something I am glad I spent money on.

Jancso, a Bolshevik film mentor and beneficiary of state interventionism in the arts in Hungary during the Iron Curtain period, literally followed the classic "September Protocol," i.e. the theoretical, Manichaeist dogma of the Stalinist Era laid out by Zhdanov and then adopted by the Communist Parties on a global scale. The first step in Leninism, after the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, was to establish, through censorship and state sponsorship, the complete control of cultural production with the aim of destroying Western thought ("Bourgeois or burzhooi", they called it) based on Jewish- Christian prophecies as well as on Roman law and Greek philosophy. In fact, all red cultural policies were born out of such distortions, namely: totalitarian Zhdanovism, engaged art, demented Gramscism, tenets of the Frankfurt School, Mao's destructive Cultural Revolution and so forth, not forgetting the message that every dictator used to state in the congresses of the communist militancy about the promotion of cultural production: "Comrades, anything for the sake of the Revolution, nothing outside the revolution!" But ¨the Round-up¨ is much more and much less than this, it is an unbearable parade of long shots where each image seems to reflect the hatred that this mediocre director always nurtured against the Austrian-Hungarian Empire.

I have made of this most notable of Hungarian films a personal holy grail ever since I laid eyes on an illustrated two-page spread found in an old British magazine of my father's entitled "The Movie" – and now, over 20 years later, I have finally managed to track the thing down and, thanks to the valiant R2 DVD label Second Run, add it to my ever-increasing eclectic home video collection. For the record, despite knowing of its imminent release on DVD, I was seriously contemplating traveling to London for last week's big-screen showing of THE ROUND-UP at the Curzon Mayfair (with Jancso' in attendance, no less) – but, alas, it is just as well that I didn't go because of what occurred over here a couple of days prior to the event: a tragically unnecessary death in the family which, worse still, turned into a national tragedy (with long-term social and legal repercussions to boot). But life, pitiless and unjust as it is, has to go on and, slowly but surely, I have now jumped back into my old routine of film watching and reviewing... Although there have been other noteworthy Hungarian film-makers before (Paul Fejos) and since (Istvan Szabo), Miklos Jancso' is still perhaps the most important. Ironically, while he was the first one I personally became aware of, my viewing of THE ROUND-UP has actually been my very first encounter with his work – although, now that the first step has been taken, it will be followed by three more in a few days' time. Sometimes it can happen to a film buff that the actual experience of watching the movie, about which one has heard a lot and eagerly longed for, turns out to be underwhelming but, thankfully, this has not proved to be the case for me with THE ROUND-UP. Indeed, the phrase "unlike anything you've ever seen before" is often freely banded about by unimaginative film reviewers – but this description is unquestionably apt when applied to Jancso''s masterpiece.In that enticing and insightful article I mentioned above written by Jancso''s first assistant director on the film itself (and which I immediately re-read upon the film's termination), it is stated that while THE ROUND-UP was based on factual events which had taken place in Hungary in 1869 and could have easily been shot on the actual locations of castles and fortresses, Jancso' sought a different visual approach altogether with regards to sets and costumes – "half-way between reality and abstraction", as he brilliantly puts it. Since I found myself wholeheartedly agreeing with other observations he made on the film, I don't see why I can't quote him some more: "It has a coherent, easy-to-read story – comprehensible at a single viewing – and at the same time a deep, intellectual, almost abstract parable".The abstraction being alluded to is not restricted to visual (literally, black and white) terms alone – where the stark whiteness of the prison-fortress walls and the hooded Hungarian convicts memorably contrast with the black capes and uniforms of the Austrian oppressors – but also to its very narrative style: while it becomes clear early on that the subject of the relentless interrogations is the identification and capture of legendary rebel leader Sandor (who never actually appears in person but whose presence permeates the entire film), people appear and disappear with insistent frequency and, although there are definite characters which take precedence over others, there is no true main central figure one can clearly identify with and root for.Thematically, it is oppression and degradation which are the key elements: right from the animated prologue at the start displaying a succession of torture devices, we later watch men made to stand in the rain and a woman stripped naked and whipped to death with canes (the sight of which sends her despairing spouse leaping to his death). But the oppressors' ultimate weapon of humiliation is treachery: through vain promises of instant freedom, prisoners – and, at one point, a grieving mother and, later still, father and son – are repeatedly induced to betray one another (via abrupt, silent motions) but, instead of liberty, they are rewarded with a bullet in the back, the retribution of their own people and, in the supremely ironic finale, cold-blooded mass extermination. In this context, the character of Gajdor is especially poignant (and even amusing in a blackly comedic way) as he pathetically keeps reminding his captors that, even though he has already fingered several worse criminals than himself, he is a prisoner still. Interestingly, this paradox can also be applied to the ingenious location of the prison-fortress (within which practically the whole film is set) – rebuilt specifically for this production in the middle of uninhabited plains that stretch as far and wide as the eye can see.Miklos Jancso' is renowned for his rigorous visual style and, even from this one sampling of his work – albeit that which is generally perceived as being his chef d'oeuvre – to say that I was rightfully impressed would be putting it mildly. The constantly moving camera, on the one hand encircling the prisoners as if it was one of them and encompassing wide vistas of soldiers astride their horses on the other, necessarily limits the utilization of close-ups to the barest minimum – as if purposefully adopting the impassive stance of an historical observer. For this viewer, it literally wove a mesmeric spell the likes of which I have only experienced once before during a movie – Robert Bresson's A MAN ESCAPED (1956) which, perhaps significantly, also deals with incarceration.

Szegénylegények is one of the best films I've seen. Even though it is not very violent or graphic, I went through same emotional scale as I did watching Pier Paolo Pasolini's Salo. Group of men, subdued and prisoned, are submitted to different traps by their jailers to find their leader. There's no way out, just another trap after another. A friend who I watched it with commented that it's like Kafka without any humor.Black & white film suits The Round Up perfectly. Contrast in photography, white buildings and dark figures give a very cold feeling, which contributes to movie's hopeless atmosphere.

Life comes along at a variable pace, and we are constantly re-positioning our gaze to obtain the optimum information in order to understand the situation we are in. This is replicated in the cinema through the mise en scène and editing of the scenes. Since the 1930s there has been an either explicit or implicit debate as to whether editing within the scene is a good or bad thing, with Andre Bazin rooting for the unity of the image against montage (editing). Fifteen years before this film, Hitchcock set down a marker with 'Rope' (and to a lesser extent 'Under Capricorn') that scenes, indeed whole films can be made without much in the way of editing, by simply organising the action and camera movement to reveal the same information in a more continuous way. Enter Miklos Jancso. With this film he became something of a celebrity in intellectually active film circles by structuring it to be shot in the main, in long takes. Does it work? Well, it works in one way, and that is that it draws attention to the Hungarian plains in which it was shot and which, during the numerous long slow pans that we see, seem to stretch forever across the landscape. Looking at it again after almost forty years, I find it difficult to believe that it made such a big kerfuffle. Long held takes DO enhance suspense - hence Hitchcock's temporary enthusiasm for them - but they seem artificial as they do not mimic the action of the eye, which is always on the lookout for something more interesting elsewhere (hence Hitchcock's enthusiasm being only temporary!). The 'rounding-up' of prisoners that it portrays is an OK subject for a film, but I think we would have been much more emotionally involved with the characters if we had been treated to reaction shots and the like. Still, see it as a theoretical/historical curiosity.