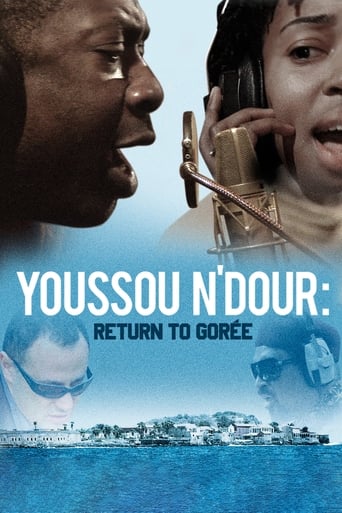

Return to Gorée (2007)

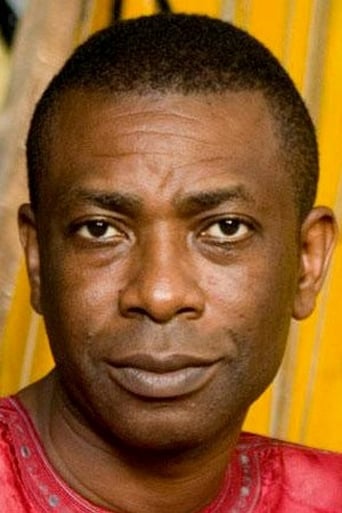

Because jazz is the miraculous product of the horror of slavery, Youssou N'Dour returned to the slave route and the music they created, in search of new inspiration. Accompanied by the blind Swiss pianist Moncef Genoud and the Director of the Gorée House of Slaves Museum, Joseph N'Diaye, the Senegalese singer wrote new songs during this initiatory voyage which took him to the USA then to Europe. At Gorée, an island just off the Senegalese coast and symbol of the slave trade, his memorable concert marked the end of this quest and the start of a new challenge: making today's generation aware of the tragedy of slavery, the importance of not forgetting and the need for reconciliation.

Watch Trailer

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

Such a frustrating disappointment

Excellent but underrated film

When a movie has you begging for it to end not even half way through it's pure crap. We've all seen this movie and this characters millions of times, nothing new in it. Don't waste your time.

This story has more twists and turns than a second-rate soap opera.

"At the bottom of the Atlantic ocean there is a rail road, made of human bones; black ivory, black ivory" The potent words of American poet, Amiri Baraka are a powerful example that nothing can begin to comprehend the history of slavery, suppression and inhumanity like music, poetry, community and love. Youssou N'Dour discovers all of these on a journey which takes him around America and back to his native Senegal on a mission to reunite the black diaspora with its history.Goree is the infamous island off the coast of Dakar which was used as a departure point for the slave trade for America and Europe. It's House of Slaves, built in 1784 still stands to this day and remains testimony to the sad history and ravaged African west coast. Yet triumphantly it is in the ruins of these cramped quarters that N'Dour has planned a concert uniting Americans with Africa, jazz with mbalax, and the present with its past.On search for the talent who will bring different elements to the musical experience, N'Dour picks up gospel singers in Atalanta, and jazz musicians in New Orleans and New York city. The individuals he meets have their own personal histories to consider, as well as that of the music they perform. A diegesis of black music is explored in analytical and historical context with discoveries of some rhythms starting in Senegalese tradition and winding up in the streets of New Orleans' Mardi Gras. Percussionist Idris Muhammed has played for hundreds of musicians from Sam Cooke to Herbie Hancock and his expertise on rhythm is unparalleled, but even he seems to have a spiritual awakening on visiting Dakar and hearing the local djembe players.There is ecstatic excitement when the various musicians are finally brought to their destination concert, in particular the three gospel singing Turner brothers who see it as a kind of 'homecoming'. Early on there is some tension when N'Dour insists that the brothers don't add a Christian perspective to his songs and an uncomfortable moment follows when the Moslem N'Dour enters the Atalanta church to perform. The Turners' journey to Goree, however, creates perhaps the most poignant scene in the documentary when they are given the tour of the House of Slaves. Standing by a portal which opens directly onto the vast ocean and the Americas beyond, they sing in harmony 'Return to Glory'. Amidst the stone walls which were used to house captured Africans for centuries this song somehow breaks down the fortress with their strength of voice and resolution. To see and hear these three proud African-Americans belting out gospel in the confined icon of the slave trade seems like victory.The music is beautiful, not just because of the strength of the performances but because they are still amplified and resonate with hardships and the hope of overcoming it. The pain of a people has been distilled over centuries into keyboards, strings and vocal chords which continues to emote in neighbourhoods and communities world wide and is palpable here in the cinema auditorium. The power of music to unite is Return to Goree's central message, but the power to move is its welcome effect.

I am the person who initiated the project of this film, I am the co-scenarist and co-producer. I would like to answer to some "Supercargo" 's comments. Sometimes, people expect too much of a film. This is obviously what happened to Supercargo when watching "Return to Goree". It was not our intention to talk about reggae and Caribbean music for instance, as it would need a whole film in itself. As well, to present where the people living in Dakar come from would need an other film, etc. We just followed Youssou N'Dour and Moncef Genoud on their quest for new musical arrangements, meetings with other musicians and a certain form of spiritual quest. About the Harmony Harmoneers song in the "Door of no Return" : it was totally unexpected, we didn't even know that they had composed a song and frankly, still today I don't know if they had prepared it or if they improvised it there, on the moment. About the so called "guards with guns" that Supercargo mentioned : Youssou was victim of a serious attempt to his live about 20 years ago, in Dakar. He has two body guards with him when he goes somewhere. They don't have guns, never. The only people with guns can be policemen. There was some of them on Goree Island the day we went there with Youssou at the beginning of the journey, and as you can imagine, they were, as many people, attracted by the cameras. That's all. We never had anybody with guns with us during the whole period of shooting in Senegal, USA, Luxembourg and back to Senegal (five weeks). About what Idris says : I totally disagree with Supercargo : Idris was saying much more with symbolic gestures, attitudes and with his silence than with words. And this is something people can feel in the movie, I believe. All in all, these five weeks turned to be a incredible spiritual experience. I was there all the time. It was great !

It is a Frank Zappa axiom that "music journalism is people who can't write interviewing people who can't talk for people who can't read." If you ever needed proof that musicians can't talk, this is the film for you. Repeated attempts at profundity stumble over themselves to end up in monosyllabic comments delivered in awestruck voices: "Wow." (Thank you, Idris Muhammed.) This film is pretentious but, while much of the pontificating from Youssou N'Dour and his gang of merry men (and one token woman) grates, the music saves the day.The main idea behind the film (what I take to be the main idea, dredged out of the inarticulate commentary) is interesting. To gather a group of musicians from America and Europe and take them on a journey through the different styles of music that grew up in and out of slavery, back to their roots in the music of West Africa, and a concert in the old slave fort of Gorée off the coast of Senegal. We are treated to gospel, blues, jazz and variations of these, including some fantastic drumming both in New Orleans and Senegal. There's also a good deal of N'Dour's own compositions.Sadly, that's another weakness. It's never entirely clear what N'Dour himself wants to achieve. To some degree, the film appears to be an exercise in self-promotion on N'Dour's part. He wants to play his own music, jazzed up to some degree and performed in the company of a bunch of musicians he admires. He's clearly a little embarrassed by this and early in the film obtains the blessings of the Curator of the Gorée museum.The clash between the different agendas shows through in several other places. For example, somebody obviously felt that it was not possible to tell the story of black music without involving a gospel choir, but N'Dour and most of his mates are Moslems (a point made repeatedly throughout the film). The whole early sequence involving the black Christians is uncomfortable and then they disappear from the story until the close harmony group (the only black Christians who can hold a tone?) turn up in Dakar at the end of the film. (To be fair, they turn up triumphantly and perform the best piece in the film.) If the story of black music needs to nod in the direction of gospel, why not also in the direction of Latin America? Where are the black musical influences from the Caribbean and Brazil? Samba? Reggae? Then there's Europe. Here the black diaspora doesn't seem to have produced any musicians of calibre, since N'Dour chooses to draft in Austrian guitarist and a trumpet player from Luxemburg. Are they in the team just because N'Dour has played with him before? What I personally found most irritating, though, was the long sequence which tried to recreate a kind of 60s beatnik/black power/Nation of Islam cultural happening in the New York home of Amir Baraka (a.k.a. Leroi Jones). Hearing people talk about the importance of "knowing your history", and then in the next breath perpetuating ignorance. Why do so many African-Americans believe that taking an Arabic name is an assertion of their African roots? And why do they think Arabic Islam is so much more admirable than European Christianity? Who do they think established the trade in African slaves in the first place? The film doesn't have much to say about the situation in West Africa today beyond the platitude that "present conditions" are a consequence of all the brightest and best having been shipped away for 300 years. The Senegalese appear to be a poor but happy, musical gifted folk, friendly and welcoming, respectful of their elders (and not above fleecing the visiting Americans in the fish market). Is this ethnic stereotyping or just my imagination? There is no comment on the armed guard that N'Dour and the camera crew seem to need in the opening sequence as they walk through the streets of Dakar.There is also a strong implication in the film that the slaves who were taken from Dakar came from Dakar. The similarity between the folk drumming style of New Orleans and the folk drumming style of Senegal is cited in evidence. The last thing the slaves heard before they were shipped away was the drumming of their homeland, bidding them farewell. Except, of course, that by and large, the slaves shipped from Dakar did not come from Dakar. They were captured or traded from the interior by the coastal Senegalese and sold to merchants of whichever European power currently held the Gorée slave fort. The people of Dakar are not the descendents of Africans who escaped the slave trade, they are just as likely more likely to be descendents of the people who sold their black brethren into slavery and exile.The two agenda's clash again in the final part of the film. There are two separate endings. On the one hand, the concert which N'Dour and Co have been rehearsing and preparing along the way and which they deliver in the courtyard of the Gorée slave fort. The other end comes when the Harmony Harmoneers sing the spiritual "Return to Glory", in the seaward doorway of the slave fort. This is deeply moving, even if it is hard to believe the performance is quite as spontaneous as it appears.This is a film that is flawed. Unclear of the story it is trying to tell and tugged in different directions. Irritating, confusing, beautiful and emotional by turns. Watch it (listen to it) for the music and the feeling, but don't expect enlightenment or intellectual rigour.

I saw this on the big screen in Austin, TX, in November 2007. My expectations weren't high; I had heard of Youssou N'Dour through his work with Peter Gabriel and liked his music well enough, but not enough to actively pursue opportunities to hear more. After seeing this documentary, my opinion of N'Dour and his music have transformed. Throughout the documentary, the twin themes of African enslavement and the liberating power of music are always in the forefront, and neither is neglected to promote the other. Instead, the themes intertwine as we follow N'Dour on his trek around the world, gathering his band of champions like a musical Yul Brenner from "The Magnificent Seven" to overcome injustice and ignorance and establish the dignity of individuals and their neglected contributions to the sad history of the African Diaspora. We are shown the musicians playing and at play, each coming across with their own distinct contribution to the cause. At every stop along the way (Atlanta, New Orleans, New York, Luxembourg, and finally Dakar) the viewer is treated to musicians performing, occasionally for audiences but often enough for each other, communicating their passions and collaborating to create something larger than themselves. And N'Dour is always around as ringmaster, coach, father figure and ambassador, providing a focus for the project; his charisma and the gentle ease with which he forms the project is a wonder to witness. Do they give out Nobel Prizes for music? But, importantly, this is not merely a didactic polemic about the evils of slavery; it is a celebration of the humanity in all of us and the expression of that humanity through music, and here is where the magic truly is. The film is at its best when we see the musicians play together and commune with each other beyond the boundaries of culture and language. When the Harmony Harmoneers sing in the doorway of the outpost that for many Africans was their last experience of Africa, you'll get chills. Seek this out; watch it with others and share in the joy and sorrow that is our collective experience, the pain that life can bring and the balm that is music.