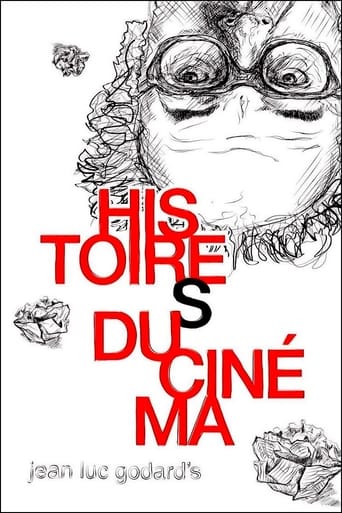

Histoire(s) du Cinéma 2a: Only Cinema (1997)

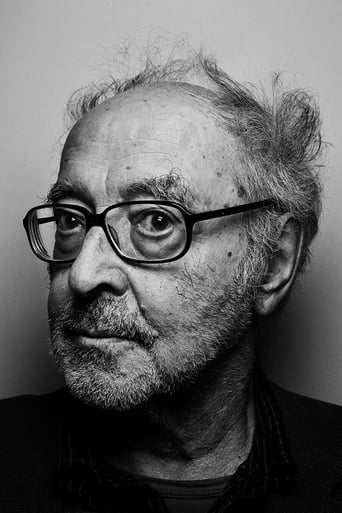

A very personal look at the history of cinema directed, written and edited by Jean-Luc Godard in his Swiss residence in Rolle for ten years (1988-98); a monumental collage, constructed from film fragments, texts and quotations, photos and paintings, music and sound, and diverse readings; a critical, beautiful and melancholic vision of cinematographic art.

Watch Trailer

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

the audience applauded

Strong and Moving!

It's simply great fun, a winsome film and an occasionally over-the-top luxury fantasy that never flags.

Blistering performances.

Years after the first two bizarre chapters of Godard's experimental video art semi-documentary project 'Histoire(s) du cinema' were released, he returned to the project w/this third chapter. For the series, it is certainly something of a change of pace and style, although it still remains highly experimental, playful, surreal, and strange, and many of the same techniques are used. This time around, however, Godard has some new things going on. Much of the earlier part of the episode is made up of Godard speaking w/film critic Serge Daney about the very project where are witnessing, discussing the histor(ies) of cinema and where Godard fits in and how to approach the overall topic. Their discussion is my least favourite part of this installment, as it feels a tad bit self indulgent and pretentious to me, however, it still delves into some very interesting topics and both men do have some rather unique and compelling observations to make. The episode gets better when Julie Delpy shows up and goes off on some poetic pseudo-monologue(s) as Godard inserts plenty of stills and clips from films like 'The Night of the Hunter' and even, here and there, 'Salo, or the 120 Days of Sodom', among many others. There's a point in which the conversation between Godard and Serge Daney returns as the Julie Deply segment continues, leading to some strange and compelling overlapping of the two main pieces of this episode. In the end, Godard has clearly crafted another fascinating and occasionally fun episode of this unique beyond belief mini series about cinema itself, of which he is most certainly one of the kings.

Only Cinema is the "a" part of the chapter two in Godard's already long-winded and underdeveloped look inside cinema through his eight-part series Histoire(s) du Cinéma. This time, we start off by having Godard annoyingly transcribe the title of this project, the chapter, and the subtitle for the chapter on a notepad with the fattest, squeakiest black marker ever. It's unnecessary and irritating and sets the tone for what we've seen so far.After the cloying introduction, however, things become a bit more solid than the first couple parts. The followup scene to the opening shows Godard being interviewed and shows him talking about working in the New Wave period of French cinema, when convention was being defined and young filmmaking rebels were popping up, showing the traditionalist approach to filmmaking wasn't the only way it could be done. The interviewer brings up an interesting point to Godard, about how the French New Wave period in film came in during the fifties and the sixties, which was also about the midpoint in cinema's existence, since it began in the late 1800's.This is an interesting thing to contemplate, being the fact that cinema was still relatively young at the time and, at least in one country, already adapted a traditionalist way of conducting itself. However, when the filmmaking rebels like Godard entered in the picture, they were almost adhering to the founders of cinema, who created their own tricks and, in turn, everything they created was subversive. Godard operated on the same wavelengths, and to this day, even still does as he churns out films and projects in his late-eighties.What follows after an intriguing interview is another array of jumbled pictures, some moving, some still images, and tiring, purposefully vague narration on how cinema relates with other different art forms. By now, it's all starting to look the same, and I'm thinking about how little I've actually learned from this. Consider Mark Cousins' massive miniseries A Story of Film: An Odyssey, which often gets criticized and discredited because of Cousins' thick, Northern Irish accent of all things. At least Cousins made a conscious attempt to hit all, or most, of the film bases and provide us with an understandable, extractable history about one of the most original and free art forms that has ever existed. It was informative and thoughtful.Godard's problem is this all feels too haphazardly planned and impulsively compiled together, as if Godard decided at the absolute last minute he'll make a series with one of the most ambitious topics and ideas ever and this is what it came to be. So far, it's a perfect example of too much ambition and too little direction.Directed by: Jean-Luc Godard.

Histoire(s) du cinéma: Seul le cinéma (1997)* 1/2 (out of 4) The third entry in Jean-Luc Godard's series is so far the worst I've seen. I'm quite thankful that the director kept this episode at just 27-minutes because had it been any longer then I would have had to accuse the director of trying to torture the viewer. I wasn't a huge fan of the first two entries but I at least got what Godard was trying to do even though I openly admit that I didn't buy anything he was saying. I'm sure many will watch them and come away with some sort of secret message that they came up with and I'm sure that's probably true with this third film. With that said, to me it's all just a bunch of mumbo jumbo that fans of the director came up with. Hey, everyone likes what they like but for the life of me I couldn't figure out what the director was wanting to say or show her. Again, I'm sure someone will come up with its message but to me the entire point of Godard is that there is no message and the mumbo jumbo is mixed up on purpose just so people can try to figure anything out. Early on we get a sequence from THE NIGHT OF THE HUNTER where we get sound effects and other pictures put across the image. The only thing this says to me is that a perfectly great film clip was ruined with nothing. We get a picture of James Dean with "destiny" written below it on the subtitle. The majority of the running time features Godard being interviewed about cinema and we see a little girl in her room rambling more nonsense.

In the final Histoires entry, Godard says "I understand better, why earlier I had such a hard time beginning, what voice had invited me to speak lodged itself in my discourse." This may refer to any number of beginnings, one of them I like to think is the false start of the Histoires films back in 1988.Godard would like to enclose all of life in cinema, long shots and short shots, pans of nature and poses on deathbeds, but in those first two Histoires films I got the sense that it was slipping from his fingers. The greatest question then of a beginning of cinema is this, where and why do we start a shot, where and why do we end it? Where do we begin to see and where do we stop, and what kind of life have we seen inbetween? As it pertains to this chronicle of cinema, where do we begin to tell the story? Godard finds premises in different things, the French New Wave included, but it's more important for me to see where these stories end, where the narrative thread is finally abandoned. It's always inwards, with introspection. This speaks as I see it of a desire for self-awareness, which he marvellously exhibits in films like Nouvelle Vague, but also an attempt of an intimate view of consciousness and soul, where all the formations of cinema are born.When this really begins to matter for me, is when Godard abandons the intellectual analysis, and instead approaches cinema with a poet's sense of awe and wonder. How the person who looks from behind a camera looks upwards to imagine starstudded worlds beyond the ephemeral, and how that glance at the divine brings about a downfall of ideas. He laments that downfall from the idea to the base desire with pornographic shots of early stag films, other kinds of violence.In the fourth Histoires, he solves for us the provocative claim that "cinema is not art, it's barely a technique". Cinema is a mystery, a mystagogy we participate in. The greatest despair of the artist then, the desperate attempt to build the imperishable and eternal from what perishes (sound, image), is at once a great dream and a great folly. Whereas once he was anxious to use cinema as a lever that participated in the discourse for a better society, now he contends himself with a flight into beauty. We take that for what we will.Mysteries for me must exist unresolved, remain enigmatic otherwise they dissolve, so to what extent shall we pursue the mystery of cinema and can we hope for a measure of liberation? Godard asks, how many films about babies, flowers, and how many about gunfire. If glory is the mourning of happiness, then the glamour of the show biz is a veil that masks something sinister. It's a mask, in the way that it obscures the true face of things. For 50 Cecil B. DeMille's, how many Dreyers? Another contradiction for Godard, but what's it worth? Perhaps the admission that cinema can obscure, with song and dance and violence, both what is good and what is bad. At this point I find myself questioning the mystery, if it can ever be means to something, or if we arrive at the core by peeling layers we find nothing.One thing is for sure, the Histoires as a whole, clocking in at 4 hours, emerges not as just a history of cinema, it is hardly that, or a story of that history, of which it is but adequate, but as a story of Godard. That is, for what Godard regales us with, he rummages through cinema to find images that correspond. Now it's James Stewart jumping in water to save Kim Novak, now it's John Wayne on horseback.It's not surprising then that these images exist, by which Godard projects his thoughts into cinema, because it's the primary reason these images exist in the first place, as a projection of thoughts, but that the notion of a story born of the abstract cinematic essentials, sound, image, motion, which can communicate the innermosts is possible.This must be the triumph of cinema then. Not that it can mirror the macrocosm, address the grand ideas and elevate us to the divine (which is a chimera), but the profound ability to speak about the small things we consider true inside of us, individually, collectively. A shot of an anguished woman, stripped off context, retains its emotional power, which is to say that the context of narrative is firstly illusionary, foremostly that something exists embedded in the image which we cannot wrestle away by any means.An image to haunt, the flickering face of Marilyn Monroe superimposed over shots of The Birds, black crows flowing out of her forehead, or inside of it. A state of mind emerges from the image, which is true both as an expression of the outside and as an impression of what's inside. The link of this, between thought and action, is karma. Godard here teaches what's possible of cinema, perhaps like no one else did before.Godard saves the greatest realization for the end, a partial answer to the questions which haunted his mind an entire career. Only when life is lived in full, with all the forces available to our body, only then can life stop questioning itself and accept itself as the true answer. Mind is the great antagonist then, a chimera.Thirtyeight years after Breathless, now I can be friends with Godard. This is a masterwork of cinema in my estimation, but I believe will be better appreciated as a work that flows from a career or life in progress, if we have a picture of who Godard was, who he came to be.