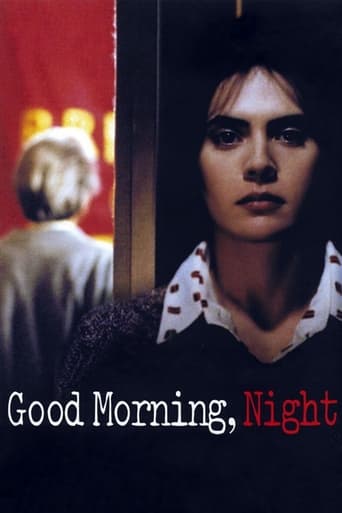

Good Morning, Night (2005)

The 1978 kidnapping and murder of Aldo Moro, president of the most important political party in Italy at the time, Democrazia Cristiana, as seen from the perspective of one of his assailants -- a conflicted young woman in the ranks of the Red Brigade.

Watch Trailer

Cast

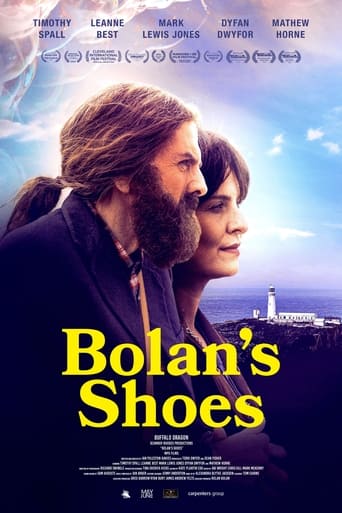

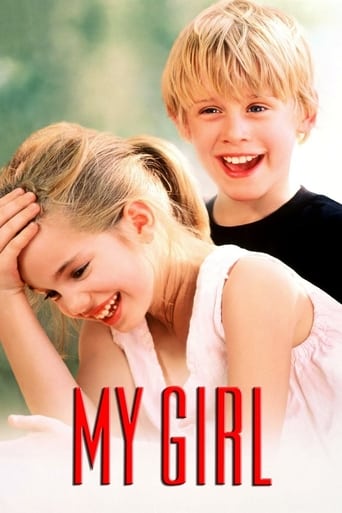

Similar titles

Reviews

Really Surprised!

Pretty Good

Pretty good movie overall. First half was nothing special but it got better as it went along.

It's the kind of movie you'll want to see a second time with someone who hasn't seen it yet, to remember what it was like to watch it for the first time.

On March 16, 1978, Aldo Moro, the Prime Minister of Italy, was kidnapped by a group of Communist revolutionaries known as the Red Brigade and held in captivity for 55 days. Through letters and photos sent by the kidnappers, the authorities learned that Moro had been given a "trial" by the Red Brigade and sentenced to death for his crimes against the proletariat of Italy - and, indeed, on May 9th of that year, his body was found, riddled with ten rounds of bullets, in the trunk of an abandoned car.In "Good Morning, Night," writer/director Marco Bellochio takes the events and drains them of much of their sociopolitical significance, choosing instead to focus on the human drama at the story's core. Bellochio looks at the ambivalent feelings and conflicted motives underlying the kidnappers' actions, particularly in the case of an attractive young woman named Chiara (confidently played by Maya Sansa), who comes to question her commitment to "the cause" as the reality of what they are planning to do begins to sink in. It is largely through her eyes that we come to view the events and to see Moro less as an impersonal force to be manipulated for political purposes and more as a simple human being with all the fears, insecurities and desperate desire for life common to us all. Indeed, the political aspects stay largely in the background, relegated mainly to clips of stock footage showing us the principal players of the time dealing with the crisis.With its dreamy visions, fantasy sequences, and tendency towards wild speculation, the film may frustrate those who would have preferred a more historically accurate, documentary approach to the topic. But Bellochio, as an artist, is less concerned with the "facts" of the case than with exploring the dilemma of the revolutionary's mindset. And to that end, he has done an exemplary job in "Good Morning, Night."

This is by no means an action movie. It's a chamber play telling what happens with kidnappers and victims, having an indeed strange relation.Aldo Moro has different effects on the terrorists and especially on the girl, the one who seems to have a normal life outside the terrorist cell, where she also encounters a normal man, which gives some tension.A strong part is played by the Pink Floyd music of the time "Shine on you crazy Diamond" and also by the authentic news rapports considering the crime and the funeral in the end. A capable although not strong movie.

I won't comment on the film's artistic merits, which I regard as noteworthy, nor on the psychological portrait given of the brigatisti, which I thought interesting but flawed. I will only say that the film was deeply moving for me and had me crying uncontrollably at times. I wish to give, instead, a sketch of the film's political context for the benefit of those whose familiarity with that period in Italian politics may be limited.By 1978 Italy had been ruled uninterruptedly for more than 30 years by coalition governments, all of which were dominated by the Christian-Democratic party (DC). The Italian Communist Party (PCI) had been thrown out of the government in 1947 (in part, on the insistence of Washington as a condition for Italy's receiving Marshall aid monies), and it was excluded from all governments even though its share of the popular vote rose with every post-war election, making it the second largest party in Italy (it peaked at more than a third of the vote in the late 1970s). The PCI was not your average Communist party. It espoused a route to the transformation of capitalism that emphasized gradualism, social mobilization, and electoral politics--and by the early '60s its commitment to the acceptance of the principles of democratic pluralism was public and pronounced. By the end of the '70s, Italy was sorely in need of reform--the kind of reform in institutional arrangements and socio-economic policies that could only come through a change in government. The 30 years of DC rule had created a regime rent through and through with corruption and unresponsive government (by contrast with the regional governments run by the PCI, which were models of efficiency and responsive government). But the US and most of the DC continued to argue that the opposition should not be allowed to come to power under any circumstances because of the "Communist menace." Aldo Moro, president of the DC at the time, was one of a few DC leaders receptive to the idea of bringing the PCI into the government to effect reforms and make the country more governable--responding, as he was, to the initiative of Enrico Berlinguer, leader of the PCI, who called for an "historic compromise" with the Catholic masses and their party. But at the same time that the PCI was inching towards the government, there were fractions of the left in Italy that felt that the PCI was selling out the dream of making "The Revolution". Certainly it was true that the PCI had long abandoned the notion of "Revolution in the West" as resembling anything like the storming of the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg in 1917 (note the imagery of revolutionary Russia thrown into the film by Bellocchio as representative of the consciousness of the brigatisti). But the PCI continued to be nominally wedded to the idea that capitalism was not the final resting place in the evolution of human social-economic systems, and that it could and should be replaced by a system of production based on production to satisfy human needs rather than private profit. The closer the PCI moved towards government and compromise with the DC, the more this commitment to a socio-economic order alternative to capitalism was put into question in the eyes of Italy's "revolutionary" left (all of which, by the way,existed outside of the PCI in other social and political organizations). Enter the Red Brigades (BR). Most of the their ranks were filled with leftists who came to "revolutionary" politics via Catholicism and the social gospel. They believed themselves to be heirs to the tradition of revolutionary militancy (and armed struggle)embodied in the Resistenza, the struggle against the German occupation of Italy,1943-45--a struggle which, in the minds of many of the combatants, was waged for the sake of a socio-economic order alternative to the inequalities and irrationalities of capitalism (it was mainly Bellocchio's use of clips showing the execution of "partigiani" (resistance fighters) and the reading of the letters they had written just prior to their execution which brought me to tears). The BR believed that through "exemplary" actions (the knee-capping or killing of politicians, journalists, and trade-unionists seen by them as enemies of the working class) they might be able to galvanize the masses of the working class, whose revolutionary militancy had, presumably, had been lulled into a quiescent state by the "sell-out" leadership of the PCI.The kidnapping of Moro was designed to put a stop to that process, and indeed it succeeded well. To the delight both of the "revolutionary" left and Washington the PCI was kept out of the government for almost another 20 years, until after the fall of the USSR and the complete dissolution of the DC under the weight of a gigantic scandal. One side note: Bellocchio is certainly in error in suggesting that Stalin would have been part of the fantasies of the BR--while they greatly admired Lenin for having pulled off the Bolshevik Revolution, they detested Stalin and the bureaucratized party rule that came in his wake.One final note: I'm not sure I understand why Bellocchio has chosen as his counter-hero a figure who suggests the use of "fantasia" as an alternative to violence. It was precisely the BR's "flight of imagination" that got them into trouble, imagining a world that didn't exist in Italy--a world of revolutionary seething masses just waiting for a spark to ignite them. In politics there's no substitute for Machiavelli's "chiaroveggenza" (the capacity to see things clearly).

The Italian national trauma of the kidnapping of Aldo Moro is a very interesting subject. A deed like that raises many questions. Why is anybody so obsessed by his ideals to kidnap the Italian president and subsequently murder him? How mentally ill is such a person? What emotions do you have when you are locked up for months in a row knowing that you'll probably gonna die? Hardly any of these questions is answered in the film. All you see is two hours of people walking through the appartment. The political discussions with Moro could give some insight in the motivations of the kidnappers but are superficial. It is as if only the uninteresting aspects of this kidnapping where filmed. There are also moving moments though: the letters of Moro to his family are heartbreaking.