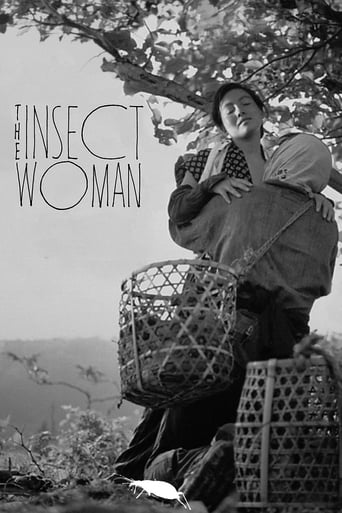

The Insect Woman (1964)

A woman, Tome, is born to a lower class family in Japan in 1918. The title refers to an insect, repeating its mistakes, as in an infinite circle. Imamura, with this metaphor, introduces the life of Tome, who keeps trying to change her poor life.

Watch Trailer

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

Terrible acting, screenplay and direction.

Excellent, a Must See

It's fun, it's light, [but] it has a hard time when its tries to get heavy.

The plot isn't so bad, but the pace of storytelling is too slow which makes people bored. Certain moments are so obvious and unnecessary for the main plot. I would've fast-forwarded those moments if it was an online streaming. The ending looks like implying a sequel, not sure if this movie will get one

Viewed on DVD. No, this is not a horror movie; just a horrible movie! Director Shôhei Imamura again documents his obsession with the sex lives of those at the bottom of Japan's social-economic food chain. In doing so, he promotes several old/new stereotypes: sex workers as role models for survival (a riff on prostitutes with hearts of gold?); the poor and ignorant being no better than insects; migrants from rural to urban environments cause big-city degeneracy because they bring it with them; etc. Pushing the boundaries of contemporary censorship (that would all but evaporate in a few years), Imamura tries his hand (and hopes to broaden his film's paying audience?) at soft porn with: simulated sex (partially hidden with poorly lit scenes); strongly-implied sex between daughter and father; adult breast feeding; etc. The film is also loopy: each succeeding generation repeats the same life process; many instances of a Capella singing with nonsense lyrics on the sound track; the opening scenes of an insert struggling to climb an incline and the closing scenes of the heroine struggling to climb a hill; etc. The net result is that the movie goes in a circle and, hence, nowhere (and also seems to stop abruptly). Acting is uneven due to an inferior script (or an over abundance of on-set improvisation?). Line readings range from grunts to micro "proverbs." Cinematography (wide screen, black and white) is hard to judge, since interior scenes are often poorly lit or not lit at all. Editing includes random bouts of freeze framing (often accompanied by comments that may be expository or just nonsense). Film music is somewhat spastic. Translations of line readings are usually close enough. Japanese film making at its worse (or darn close to it!). WILLIAM FLANIGAN, PhD.

The Insect Woman (the original title translates to Entomological Chronicles of Japan) is possibly the most ambitious out of Shohei Imamura's B&W films. It's a near-epic historical drama with a satirical undertone, jumpy storytelling and a wide array of characters. It stars Sachiko Hidari, one of the best Japanese actresses of the '60s, in a role of her lifetime, and the rest of the cast is usually compiled out of Imamura's regulars, like Jitsuko Yoshimura, known for Imamura's Pigs and Battleships and Shindo's Onibaba.Imamura's films, especially this one, Intentions of Murder and The Ballad of Narayama, like to compare the various types of people with respective animals. This movie starts with a beetle trying to climb a mountain of dirt and ends with a shot of the protagonist, Tome, trying to get on the top of a hill. So why exactly does Imamura compare her with insects? Because throughout all her schemes and woes, her moments of being oppressed and being the oppressor in a chaotic society that's hard to adapt to, she never really gets anywhere, or if she does, it's temporary. She is forced to repeat her mistakes over and over again and adapt to the fast-moving world as best as she can. Even her lineage is cyclical; she was born a bastard child, had a bastard child, and then her bastard child got a bastard child.The movie's plot spans throughout the first half of the 20th century and Tome herself is almost paralleled with Japan itself, as she goes from a simple peasant girl to a crafty businessman. Imamura was fascinated with irrationality, sensuality and passion still alive in traditional Japan, and Tome, like many of his heroines, is a personification of that animalistic lifestyle. Imamura's characters are passionate, sexual, hot- blooded, fickle, adaptable and impulsive, and his the way he portrays women is almost like a counterpoint to Mizoguchi's typical fallen woman who sacrifices herself for whatever she has in life. Imamura's characters will do anything to get ahead, but they still have their basic moral codes and principles to keep them going.The cinematography is, like in Imamura's other stuff, "messy", as he liked to call it. The stillness, taming and concealment of naturalistic tendencies of his mentor Ozu's films are replaced by stuffed shots of various sources of light, multiple characters on screen at once, and a chaotic exchange of camera techniques imitating the characters' hasty libidos, making the movie look very modern. This is, for example, noticeable in the sect headquarters scenes (more like The In-Sect Woman! Ha!). Another interesting thing about the movie is how ballsy it is concerning the depiction of themes like poverty and incest (more like The Incest Woman! OK, I'll show myself out now...), especially for the time.This is the epitome of a "good" movie. A straight pace, excellent photography, believable acting, the underlying messages and a dash of modernity all make it a good film by all standards. The only factor by which anyone could really rate it is whether or not the story interested them or not.

First seen around 50 years ago by the eccentric old Japanese gent sat next to me (who mysteriously managed to lose his cap inside his own bag at the end of the film), 'The Insect Woman', to give it its English title, charts the rise and demise of Tome from her birth to middle-age in post-war Japan. Born a bastard (or bitch, if she's a lady), she forms an unusual relationship with her father while growing up in a small village out in the sticks. When becoming a woman, she grows more rebellious, giving birth to her own bastard daughter and becoming further shunned by local gossip, and so moves to Tokyo to take her childish rebellion to the world of prostitution, whoring out anyone she meets.Made in 1963, director Imamura Shohei creates a quirky film full of subtle humour, with its tongue firmly in its cheek. With a controversial back catalogue behind him, this film is full of naughtiness and shows a modern woman not afraid to throw herself into anything in the hope that her daughter will not lead a similar life to hers.Taking on social taboos, the influence of this piece can be seen in the many later films tackling women fighting alone against society's pointing finger, and for that, the digital re-mastering is justified 49 years on. Full of humour and entertainment value, this is an important work in the career of an influential Japanese director whom passed away last year: a friend of my fellow eccentric old Japanese audience member.

THE INSECT WOMAN is essentially a rags-to-riches-to-rags story told in fragmentary style against a backdrop of significant historical events of 20th Century Japan. The film's title (it also goes by the more clinical name of ENTOMOLOGICAL CHRONICLES OF JAPAN!) remains obscure, however, unless the director wants to assimilate Japanese women to hard-working (i.e. slave-like) insects. Indeed, leading lady Sachiko Hidari (an excellent, award-winning performance) slowly rises from the position of simple prostitute in an exclusive brothel to that of - the equivalent of a Queen Bee, one assumes - madam of said establishment (eventually being replaced by her own daughter!). There is also a subtle hint of incest here, with the woman's father showing an unhealthy interest in her growing up - an affection which is then transferred to the daughter, once she leaves the country for the big city! Another interesting, if entirely gratuitous, touch is the director's idiosyncratic (since it is heavily featured in all 3 of his early films I've watched) use of freeze-framing as a means of transition from one scene to the next.