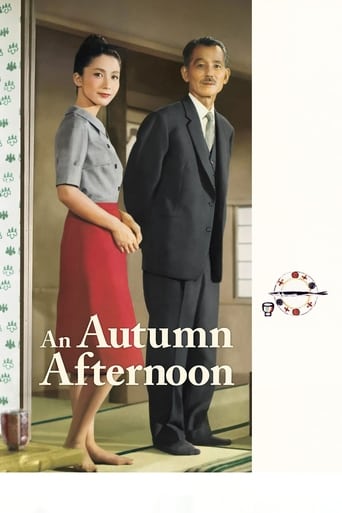

An Autumn Afternoon (1962)

Shuhei Hirayama is a widower with a 24-year-old daughter. Gradually, he comes to realize that she should not be obliged to look after him for the rest of his life, so he arranges a marriage for her.

Watch Trailer

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

Sorry, this movie sucks

Great movie! If you want to be entertained and have a few good laughs, see this movie. The music is also very good,

There's no way I can possibly love it entirely but I just think its ridiculously bad, but enjoyable at the same time.

While it doesn't offer any answers, it both thrills and makes you think.

AN AUTUMN AFTERNOON is a drama which examines family relationships and life decisions in a warm way.The main protagonist is an ageing widower with a 32-year-old married son, and two unmarried children, 24-year-old daughter, and 21-year-old son. His wife has died just before the end of the war. His older son lives modestly with his wife in a small apartment. The widower and five of his classmates from middle-school hold regular reunions at a restaurant. They remember their old times and having fun with good food and drink. One of his friends has found a good opportunity for his daughter. She takes care of the housework, drunken father and younger brother. After a few events, the old man recognizes his own selfishness in keeping his daughter at home to look after him, and decides to arrange a marriage for her...Mr. Ozu has made another family drama that touches the soul. He examines topics related to a family, loneliness, alcoholism, marriage, through relationships between parents and children. His emotional space is narrowed to everyday life, in which a thin line separates the joy and the sorrow. He points to the transience of life through a family melodrama.The scenery is almost closed and spatially confined, that suggesting a monotonous daily routine. The characterization is excellent.Chishū Ryū as Shūhei Hirayama is a reserved and quiet old man who finds moments of his happiness in having fun, alcohol and beautiful owner of a bar. He skillfully hiding his inner emotion. He has tried to resist the transience of life, of course, to no avail. Shima Iwashita as Michiko Hirayama is his devoted daughter. She is aware of her situation, but unhappy at leaving his father and brother. Keiji Sada (Kōichi Hirayama) and Mariko Okada (Akiko Hirayama) are very entertaining as a quarrelsome couple, which is burdened with a material world. Anyway, life goes on.

"An Autumn Afternoon" is Ozu's last picture and probably his most bitter. In his other movies, sorrow was generally compensated by some caring characters or an affectionate relationship. Here, nothing really positive emerges. The plot is similar to the one of "Late Spring" (1949), where the same actor also played a widower persuading his daughter to marry; however, "An Autumn Afternoon" is darker, with more social insight.The original title ("The Taste of Mackerel Pike") is low-key, mysterious and meaningful, somewhat like Ozu's films. It refers to a fish that is widely eaten in Japan, especially in autumn when it is abundant: its taste is bitter (if eaten whole as Japanese frequently do for this species); and autumn evokes a world that is changing, possibly decaying.It is a post-war movie, even though it was shot 17 years after WWII, in the sense that an emerging society tries to find its path within a modern world. There are many references to the war: Hirayama went to the Naval Academy; Hirayama and Sakamoto were on a warship; they discuss about war, as well as other customers later on; a jukebox plays a patriotic song twice (the Navy Hymn) and Hirayama sings it at the very end; Hirayama, Sakamoto and the waitress imitate the military salute; we understand Hirayama's wife died during WWII. The country faces mourning, humiliation of defeat, development challenges. Yet the society that emerges is void: it displays solitude, acrimony and materialism.Solitude is a dominant feature. Characters talk about professors and spouses who disappeared. Hirayama and Sakuma are widowers; a barmaid reminds Hirayama of his late wife. Hirayama, Kawai and Horie make jokes about death and refusal (see below). Hirayama is left alone at the end, drunk and depressed; his last words ending the movie are: "Lonely in life". Michiko is turned down by the man she loves. The plot then tends towards her marriage with another man, which should be good news; however we never see the ceremony and not even the bridegroom at any point: we just see Michiko in her wedding dress, silent and sad. Symbolically, she is still alone. After he comes back from the wedding, the barmaid asks Hirayama, "Were you at a funeral?" to which he tragically answers: "Sort of". It could be his own funeral since he is now lonely, or his daughter's, buried in a marriage that could turn out as the other couple's (see below).Even when characters are not alone, relationships are cruel. Koichi and his wife Akiko always argue; there is not one single sweet moment between them, despite the fact it is the only couple we see (Horie's wife only appears briefly). Hirayama is frequently scolded by his children, even though he is a decent man. Koichi lies to him about the money he needs to buy a fridge. Tomoko despises her father Sakuma. Sakamoto says about Sakuma's noodle bar, right in front of him: "It's ugly here, let's go elsewhere." People frequently leave gatherings earlier than expected, spoiling the atmosphere; notably, Horie unexpectedly leaves the dinner with Hirayama and Kawai, despite the fact Kawai cancelled a baseball game to attend. These so-called friends play nasty jokes to each other: Hirayama and Kawai make the waitress believe Horie is dead, while he is only late; afterwards, Kawai and Horie make Hirayama believe his daughter will not be able to marry the man they recommended, which saddens Hirayama, but it is a lie.And when relationships are not tense, they are shallow: conversations are mostly pointless; people drink a lot when they are together. Worse: left to their own fates, individuals have nothing valuable to hang on to. Knowledge is not praised any more: the former respected professor Sakuma is now obliged to run a cheap noodle restaurant to make a living. Lifestyle is disrupted; many activities relate to Western culture, not Japanese: Sakamoto complains American culture has invaded Japan while drinking a whisky in a bar with a Western name! Characters also watch baseball or play golf with American branded clubs. The main exception is the aforementioned patriotic song, but that scene is highly ironic since Japan lost the war. The only tangible element that dominates is materialism. Koichi and Akiko mostly think about buying a fridge, golf clubs, a handbag Akiko covets a vacuum cleaner at a friend's home. Notice how overall the movie is smooth: there are no loud noises, nobody shouts, we barely hear the city despite the fact we are in the middle of Tokyo. Precisely, the only exceptions are loud noises coming from material elements symbolising consumption: golf balls against the practice metal net, a jukebox, a syrupy off-screen music ironically playing when people go out to drink. Likewise, the most striking images are void of persons: the movie opens with shots on a huge factory with fuming chimneys; throughout the movie there are repeated "empty" shots, notably of bright neon signs outside the bars; we do not only hear the golf balls striking the metal net, we see them distinctly; the movie ends on other "empty" shots.As a result of all above, persons are frequently sad: Hirayama, Michiko, Sakuma, Tomoko. The only relief is getting drunk. Amid this vacuity, only does the main character Hirayama understand his country has taken a wrong path. In a stunning remark that must have thoroughly shocked Japanese 1960s audiences, he admits to Sakamoto: "It is maybe better we lost the war" (instead of invading the USA with their culture if Japan had won instead). Nobody else seems to mind. For instance two customers in the bar shockingly laugh when they mention Japan was defeated: who cares as long as we can drink, they seem to think.With "An Autumn Afternoon", Ozu asks: where have we gone? We could have built a brand new society with values, solidarity, hope; yet exactly the opposite happened. A bitter testimony that could still be valid nowadays.

An aging widower arranges a marriage for his only daughter.This was the final film of Ozu, who had been making great cinema for decades. His 1930s silent crime dramas are excellent, and everything after is worth a watch. For his final film, it gets a bit more modern. We have a young woman who really is not all that interested in getting married. How can it be that finding a suitable husband is not the first thing on hr mind? The framing and colors are excellent, and very much evoke the best of the 1960s. How Japan was different from other places at the time I do not know, but in some ways the worlds do not seem far apart. This could take place at an American office in the 50s or 60s. Well, without the bowing, anyway.

I can whole-heartedly relate to previous reviewers' sentiments about this movie. From my own perspective it is also an awesome celebration of beauty. The theme is the same Ozu's favorite—separation of father and his grown-up daughter-- however it is presented in a different, less nerve-wrecking and more humorous way (as compared to Late Spring), but most of all -- within the colorful kaleidoscope of everyday things looking as works of art in themselves. Ozu rejoices in showing the beauty of such mundane objects as mugs, bowls, kimonos, tables, lamp shades, houses, fences, even industrial chimneys and such. Colors and shapes are arranged into perfect compositions and sometimes it seems that still objects actually govern the mood and the flow of people around them. The parallel with Tarkovskij's movies, like Solaris and Stalker, where the harmony of individual objects creates its own layer of movie symbolism, seems natural, only Russian movies were shot more than a decade later. I watched An Autumn Afternoon several times with the same joyful interest and gratitude for the gift of showing us the beauty of everyday life.