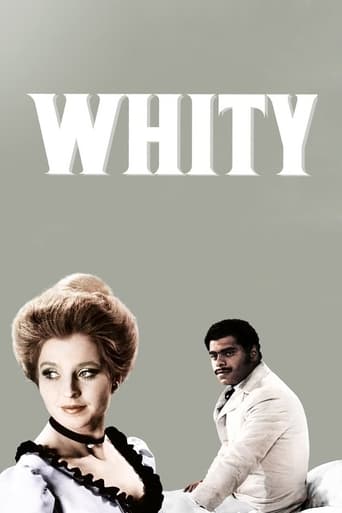

Whity (1971)

"Whity" is the mulatto butler of the dysfunctional Nicholson family in the American southwest in 1878. The father, Ben Nicholson, has an attractive young wife Katherine, and two sons by a previous marriage; the homosexual Frank, and the retarded Davy. Whity tries to carry out all their orders, however demeaning, until various of the family members ask him to kill some of the others.

Watch Trailer

Cast

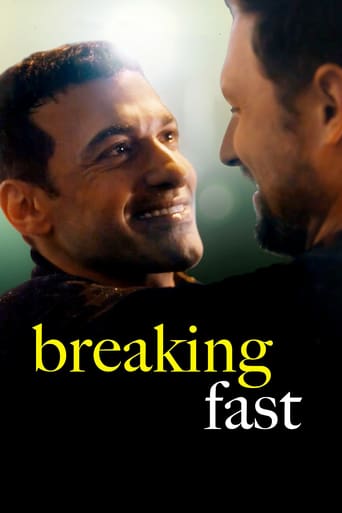

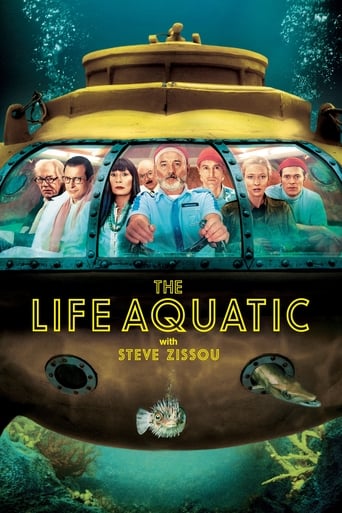

Similar titles

Reviews

Save your money for something good and enjoyable

All of these films share one commonality, that being a kind of emotional center that humanizes a cast of monsters.

The tone of this movie is interesting -- the stakes are both dramatic and high, but it's balanced with a lot of fun, tongue and cheek dialogue.

One of the film's great tricks is that, for a time, you think it will go down a rabbit hole of unrealistic glorification.

Never released commercially, 'Whity' remains one of Fassbinder's least seen films, and when spoken of it is usually with mild incredulity since the thing is reportedly a western. Naturally it's a western the like of which English-speaking audiences have never seen before (or at any rate since 'Red Garters'), but one that would look less eccentric to a German audience used to the popular Karl May adaptations of the sixties in which men are men and women are German. Although there are nods towards Sergio Leone - notably with Peer Raben's score - it plainly owes more to Gillo Pontecorvo's 'Queimada!' (1969) and to the 'slavery' genre of the seventies that began with Herbert Biberman's 'Slaves' in 1969 and reached its apotheosis with 'Mandingo'. Sumptuously designed by Kurt Raab and fluidly shot in widescreen and Eastmancolor by the late Michael Ballhaus, visually it anticipates the saturated colours of Fassbinder's final extravaganzas like 'Lili Marleen' and 'Querelle' with the cast resembling waxworks. It effectively does for westerns what 'Der Amerikanische Soldat' did for gangster movies, but is far less fun; although Fassbinder's own appearance as a macho, whip-wielding cowboy is as funny as anything to be found in 'Carry On Cowboy'.

* For people who haven't seen the film I recommend skipping the first part of the comment to start reading right at - The Style - * What's noteworthy is how much more this relatively early Fassbinder has in common with his later films such as the BRD trilogy than with anything he did before. For example the fact that the main character is trying to integrate into a family/society against all odds, with fatal consequences. Not only do those families/societies reject the main characters of the RWF films in question, but those systems turn out to be miserable and integration into them turn out to be undesirable. The propagated Weltanschauung is downright pessimistic, with no realistic hope anywhere in sight.So the movie's title character Whity is trying to integrate, even to the point of lacking much of a personality. He doesn't care if he is black or white, or even straight or gay, he just wants to be a part of something that is bigger that himself.The Themes - Interestingly the film doesn't seem to be much concerned with racial issues. I don't see Whity to be representative of the black man in America, but rather it uses a black man in the West as an example of slavery and a man who tries to integrate into a system that doesn't want him for superimposed reasons, all the while he is more competent than most other people around him.The (white) members of the Nicholson family all have makeup that makes them look sickly pale, which could be to empathize those people's degeneration, compared to Whity. They are free, he is not, they have power, he hasn't, purely because of superficial reasons and not because they are actually stronger.What's also important is the capitalism versus love theme. In the family everyone is ridden by greed, money is their biggest concern and this reflects their decadence. Whity doesn't have much desires at all, he is the best example of happiness in slavery. He doesn't know a better life, so he is satisfied with his position. That was until he found love. It's partly through this love that he realizes the degenerated state of his family (the Nicholsons) and it's love that is enough of a substitute that it makes him want to radically leave behind his family in the end.But the movie doesn't give a solution for Whity's tragic situation, in the end he leaves the system that he fought to be a part of all along, just to go into the vastness of the desert (a non-system, if you will, a place where money and power doesn't matter), just to die, suggesting that there in fact is no solution, other than death. This is why I find the film to be extremely pessimistic. Whity has found love, but not only is it not considered a solution, but it implies that there is none, by Whity consciously deciding to end his life, basically.The Style - As for the style, obviously the film is much more inspired by Spaghetti Westerns than by American ones, which starts with the opening credits with the names flying towards the audience, and continues with the intentionally slow-paced nature of the film, its melancholic atmosphere, and the exaggerated ambient sound. In fact, it's directly reminiscent of Leone, but the big difference is the small scale of RWF's film. I found the slow pace more tedious than anything else. It's too much of an imitation and not enough its own thing.As good as Ballhaus' camera work is on its own, the concept of frozen subjects captured in fluid images doesn't work well if there is little (appropriate) content to back it up, not to mention that this is pretty much the opposite of Leone's cinematography, which is mostly rigid camera where even the smallest protagonist movement looks epic. If Leone's camera moves it is to follow the protagonist, not to pan to another protagonist. He fearlessly employed a cut to show another character, which made every character the star of his own shot.The Resume - Although the film certainly isn't devoid of appealing themes, the way it is I can't say that it tells an interesting story. Apart from Whity all the characters are just too empty, they are just pawns in Whity's story, which wouldn't be as bad if there weren't so many scenes in which he isn't much more than a spectator or isn't even present.As implied before, the content simply doesn't lend itself to a Leonesque Western. A Leone Western lends itself to strangers being unpredictable, danger-laden atmosphere and situations, and gunslinging, it doesn't lend itself to internal family affairs, everyday life and character studies. I would consider 'Whity' a failed experiment, Fassbinder's story-telling sensibilities combined with an imitation of Leone's style is a system into which integration is undesirable.

When is a Western not really a Western? When it’s directed by Fassbinder! WHITY is only my sixth film from the so-called German wunderkind: I admire Fassbinder for his prolific and versatile output, though I’ve yet to be won over completely by a film of his; frankly I was hoping this would prove to be the one – but, as it turned out, I couldn’t have been more wrong! For the record, I’ve got four more titles from him to watch: still, considering my dismal experience with WHITY (especially since I had fully expected it to be the most accessible of the lot!), I don’t know when I’ll muster the courage to get to them now…even if DESPAIR (1978) is a reasonably enticing title, given the participation of Dirk Bogarde and the Vladimir Nabokov source.To be fair, the Western ambiance is delivered in spades throughout. The film was stunningly shot in Widescreen – by Michael Ballhaus (later a valued collaborator of Martin Scorsese) – in Almeria, location site of many a Spaghetti Western. It generally has the right feel for time and place with regards to settings and wardrobe, while the all-important score is highlighted by a decidedly infectious riff. Even so, the repertoire of English-language ballads (the bulk of the film, of course, is in German) allotted to chanteuse/prostitute Hanna Schygulla – not to mention her own affected delivery – is inappropriately modern and comes across as unintentionally laughable! Schygulla was a fixture in Fassbinder’s work; the film also features Ron Randell (best-known, if at all, for playing Christ’s attorney[!] in Nicholas Ray’s KING OF KINGS [1961]) and Ulli Lommel (who later graduated to directing himself, notably TENDERNESS OF THE WOLVES [1973] and THE BOOGEYMAN [1980]).The overriding pretentiousness at work here is palpable above all in the film’s lethargic, indeed deadly, pace (never have I seen a movie in which the characters moved more s-l-o-w-l-y!). Besides, it isn’t helped by unsympathetic (even annoying) characters – mostly members of a dysfunctional family (and particularly the pasty-faced, frizzy-haired sons of landowner Randell) – indulging in all manners of transgressions (from such commonly-depicted capital sins as greed, lust and murder down to nymphomania, masochism, interracial relationships and incest!). In the midst of all this is an unsavory gay subtext which, inevitably, seems to be on the agenda of virtually all directors so inclined in real-life (but becoming obviously more pronounced in the liberalized modern cinema)! The plot, for what it’s worth, is reminiscent of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s THEOREM (1968) – coincidentally another gay parable – as the life of everyone involved is influenced in some way by the household’s black manservant (the character bears the ironic titular nickname but is also curiously underwritten and inexpressive), who’s actually the fruit of Randell’s illicit affair with his frumpy colored maid! The fact that each, in turn, pleads with him to slay the other could have turned this into a pointed black comedy – but the film is simply too labored and deliberately self-conscious for the subtlety intrinsic to such refined treatment... In the end, one should note that 1971 saw a boom of arty Westerns with other such offerings as Alexandro Jodorowsky’s EL TOPO, Peter Fonda’s THE HIRED HAND and Robert Altman’s McCABE AND MRS MILLER. As for WHITY (whose shooting, by the way, inspired Fassbinder’s own BEWARE OF A HOLY WHORE [1971]), I had owned the Fantoma DVD – which includes an Audio Commentary from Ballhaus and Lommel – for quite a while before actually sitting down to view it. I’d purchased the disc through the company’s own website during a sale but, as I said, could only manage to find a slot for it in my hectic/eclectic schedule after having enjoyed a couple of equally stylized (but far more satisfying) Spaghetti Westerns – DEATH SENTENCE (1968) and YANKEE (1966) – earlier this week.

Rarely screened, forgotten by even the most devoted admirers of Fassbinder, _Whity_ is nonetheless a crucial film in Fassbinder's own development as a film-artist. For one, the style of the film marks Fassbinder's turn away from his earlier, Neo-realistic efforts (notably _Katzelmacher_ and _Why Does Herr R. Run Amok?_) and turn towards the flamboyant, melodramatic form favored by him until his untimely death in 1982. Melodrama turns out to be the best possible style for the film's story, which chronicles the fall of the seigniorial Nicholson family in the Mexican 19th century. Indeed, this film should be seen for no other reason than the inescapable weirdness one feels in watching German actors play Mexicans in the Old West. It's like seeing Peter Lorre playing John Wayne: ridiculous, if only it weren't so creepy. "Decadent" and "dysfunctional" are words redefined by the Nicholson family: the patriarch, Ben Nicholson, is remote and cruel, the wife a nymphomaniac, the older son a flaming homosexual, and his brother a severely retarded adolescent. Then there's Whity, the ironically named mulatto slave of the Nicholson family, an inadvertent focus point of each family member's perverse obsessions. It is this mutual obsession with Whity (an obsession shared by the viewer by film's end) which allows Fassbinder to explore the themes which were to comprise his greatest contribution to film's development as a medium, including: dominance and submission, the role of the Other, sexuality, the doppelganger, the economy of familial relationships, and the obstacles fate puts in the way of consumating love. These issues gain complexity when one considers that the slave Whity is played by Fassbinder's then-lover, Gunther Kaufmann. Given this, what is the viewer to make of such stylistic scenes as when Whity is disciplined by his master, while the other family members garrulously look on--knowing that Fassbinder himself is also watching from his director/dictator's chair? (The complex inter-relationships of Fassbinder and the actors during the filming of _Whity_ were later chronicled by Fassbinder in his film _Beware of a Holy Whore_, which is based on the real-life melodrama that occurred _off_ the set of _Whity_.) If nothing else, _Whity_ deserves to be included in with the other Fassbinder films, such as _Despair_, which are so justly celebrated for their psychological depth and complexity. Beyond this, two aspects of Fassbinder's technique in making _Whity_ deserve special mention. The first is that in _Whity_, one of the first of his films to employ a half-way reputable color process, Fassbinder shows himself to be a great colorist in the tradition of Delacroix, bathing the eyes with the lushest oranges, browns, and reds to be seen this side of a sunset. The palette is one that seems to have existed in film only in the late 60s and early 70s, finding similarly gorgeous expression in Truffaut's _Fahrenheit 451_, Boorman's _Point Blank_, Godard's _La Chinoise_, and Nicolas Roeg's early efforts (_A Funny Thing Happened On the Way to The Forum_ , _Performance_, _Walkabout_, _Don't Look Now_, _The Man Who Fell to Earth_). The second aspect of noteworthy technique is a camera movement that truly has no precedent in film history--a fact which makes the obscurity of _Whity_ among film scholars all the more remarkable. The best example of the technique occurs in a scene in which Ben Nicholson reads his last will and testament to the silent family members surrounding him. During an unbroken ten-minute take, the actors remain virtually motionless, as if posed in some Rembrantian tableaux (and in this way recalling Dreyer's _Day of Wrath_). Against this stasis, the camera pans slowly from one family member to another, following their own sight-lines, as if the camera were recording the trace of their attention. For ten minutes the camera repeats this zig-zag path with methodical precision, while psychedelic, trance-inducing music drones in the background. The greatest merit of the technique (seen also in an equally static scene between Whity and the retarded son in the horse barn) is that it allows the viewer time enough to meditate on the relationships among the characters involved in the tableaux--in this case most profoundly on the relationships of power among family members. It's as if Fassbinder, using film technique, took a snapshot of the family, and then spent ten minutes tracing out with his finger exactly who is dominated by whom, who resents the domination, who is perceiving whom and how, and so on. The technique, which to my knowledge Fassbinder never used again to such great effect, can only be seen as the great innovation that it is, and as such, a powerful tool for the revelation of psychological truth. However, let none of these deeper concerns eclipse the enjoyment to be had watching this bizarre, Teutonic _Dallas_ unfold. Like the best moments in a Warhol film, the high camp of _Whity_ is very, very funny to watch--certainly because it is absurd, which is not to say it is without profound meaning.