A Dry White Season (1989)

During the 1976 Soweto uprising, a white school teacher's life and values are threatened when he asks questions about the death of a young black boy who died in police custody.

Watch Trailer

Cast

Similar titles

Reviews

It's entirely possible that sending the audience out feeling lousy was intentional

It was OK. I don't see why everyone loves it so much. It wasn't very smart or deep or well-directed.

Good films always raise compelling questions, whether the format is fiction or documentary fact.

Worth seeing just to witness how winsome it is.

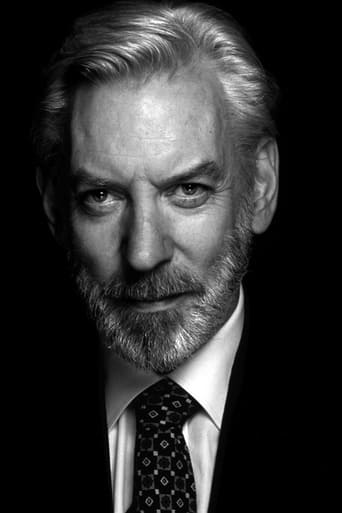

It took the cause and message of A Dry White Season for Marlon Brando to leave his self-imposed exile in Tahiti to come back to the screen, albeit in a small supporting role. Still the cause was one of the most remarkable in the 20th Century, the eventually successful opposition to the white apartheid government of the Union of South Africa.A Dry White Season was originally a novel concerned with the aftermath of the famous Soweto Massacre when South African troops fired on a protest of black Bantu children being forced to learn in Afrikaans the language of the oppressor as Desmond Tutu so eloquently put it.The son of the gardener at Donald Sutherland's estate is killed in Soweto and his body is not returned. After which the gardener Winston Ntshona is picked up by the special branch of the South African Police for asking too many questions and later he dies in prison the result of a suicide which no one with a functioning brain believes. At that point Sutherland decides to intervene himself.Sutherland plays a history teacher in a white only school and as he learns about what's going on and starts asking the questions he dare not ask before even to himself. His radicalization is total, but it costs him dear, his wife Janet Suzman and his daughter Sussanah Harker leave him, but his young son Rowen Elnes sticks with dad.It's not that he doesn't gain a few new friends, African National Congress organizer Zakes Mokae, crusading journalist Susan Sarandon, and human rights attorney Marlon Brando. But he also gains a bitter and malevolent enemy in Special Branch Captain Jurgen Prochnow who apparently does damage control for the government. That includes outright murder of suspected opposition to the apartheid government.Every actor worth his salt loves a courtroom scene and Marlon Brando might have even come back for that in this film as well as the anti- apartheid cause. He got the film's only Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor, but lost to Denzel Washington for Glory. I suspect given Marlon's history with Oscar folks were reluctant to vote for him.The film really belongs to star Donald Sutherland though and I think it a pity he wasn't given any Oscar nomination for this fine film with an eternal message about freedom.

This movie explores apartheid and the monstrous injustices perpetrated against non-white South Africans by that system from the perspective of Ben du Toit (Donald Sutherland), a well-respected history teacher of Afrikaans heritage (white South Africans are primarily Afrikaans (of Dutch descent) or of British descent). Ben du Toit is portrayed as a decent, law-abiding man who investigates the death of his gardener, Gordon Ngubene (Winston Ntshona). Ngubene dies in police custody while investigating the circumstances that led to his son first being whipped across the buttocks and then being killed by the police. At first, du Toit merely approaches the police in good faith, politely expressing concern to Colonel Viljoen (Gerard Thoolen) and Captain Stolz (Jurgen Prochnow) together with the observation that human errors do occur, even at South African police headquarters.With the aid of Stanley Makhaya (Zakes Mokae), du Toit gathers evidence revealing, unambiguously, that the police had tortured and murdered Ngubene in scenes of stomach-turning cruelty. Du Toit goes through profound psychological turmoil as he realizes that the government and the police in which he had placed so much faith were instruments in the service of massive oppression, made all the more personally horrifying in that this oppression had allowed du Toit and others like him to live their lives in relative comfort and complacency, never having to observe the brutality and barbaric actions taken in the service of preserving that comfortable lifestyle, yet alone having to account for it. With the aid of British reporter Melanie Bruwer (Susan Sarandon), du Toit gather sufficient evidence to bring criminal charges against the "Special Branch" of the South African Police.Barrister Ian McKenzie (Marlon Brando) agrees to take du Toit's case, knowing in advance that the case will never succeed. Brando steals the show as he informs du Toit that the law and justice are "second cousins," and that in South Africa they are "simply not on speaking terms." The courtroom scenes are riveting, as McKenzie slowly but brutally exposes the horrifying manner in which Ngubene was murdered. Viewers should be prepared for a chilling account of the state of Ngubene's body as, for the first time during the trial, McKenzie raises his voice and lambasts the "Special Branch" for their handiwork.Unknown to du Toit, his wife Susan du Toit (wonderfully portrayed by Janet Suzman) had sneaked into the courtroom to watch the proceedings. The reaction of du Toit's family is mixed -- daughter Suzette du Toit (Susannah Harker) and wife Susan are furious with Ben, who is supported only by his son Johan (Rowen Elmes). In a scene that is profoundly disturbing precisely because of the sincerity of her beliefs and the validity of some of the points that she makes, Susan compares life in South Africa to life during a time of war, and exhorts Ben to choose the side of his people. She grapples with her conscience as she acknowledges that she does not believe that everything that the police does is right, bur she is adamant in her determination that Ben must reject the viewpoint of the black majority, even if that means rejecting the truth. She does not even try to hide her racism as she complains about not wanting Gordon's ghost to haunt her house; how she does not want "any of these kaffirs" in her house ever again, echoing daughter Suzette's comments about the newspaper photograph of Ben and widow Emily Ngubene leaving the courtroom ("Pa! You with a kaffir woman! You look like lovers!").Having failed to bring the government to account in criminal proceedings, du Toit decides to file a civil suit. He is supported in this endeavor by Stanley, Melanie, and his son Johan. However, against the backdrop of approaching Christmas, matters are fast spinning out of control. He is fired from his job as a teacher on the pretext of having missed too many classes. When he dismisses this pretext and demands to know why he has been fired, du Toit is informed by the headmaster that it is "a matter of loyalties." When the headmaster informs him that it would be better were Johann not to re-enroll at the beginning of the next term, stating that the school does not need traitors, du Toit literally backhands him across the face in what is certainly one of the movie's most satisfying moments.Stanley arrives at the du Toit residence on Christmas Day, stinking drunk. Emily Ngubebe has been killed -- she died trying to prevent her children from being deported to Zululand (one of the "Bantustans" created under apartheid). The Christmas party is ruined as du Toit's few remaining friends leave in disgust and outrage, and Susan leaves the house, uttering the thoughts that had, until that moment, been unstated by so many of du Toit's Afrikaaner friends ("What a pretty picture! A drunken kaffir and an Afrikaaner traitor. You deserve each other.") Events lead to a bitter climax in the remainder of this movie. Realizing that there is no longer time to file a civil suit, du Toit has to find a way of handing all of the evidence that he has uncovered (most of it in the form of affidavits) to the liberal South African newspaper ("The Rand Daily Mail," which was indeed a liberal paper until it closed shortly before the writer left the country). In a scene of searing sadness, du Toit relies on the knowledge that his daughter Suzette will betray him to send the police on the chase of a decoy.In terms of authenticity, this movie's faults are minor. Flaws in accent are minor in what is otherwise an incredibly sad unveiling of the human suffering beneath the lies; of the savagery that permitted du Toit and all white South Africans to live as they lived; and of the personal cost to those who were brave enough to dissent.

Apartheid gripped South Africa for many years. One heard the news with total disbelief, as things got worse in that country. Euzhan Palcy has brought Andre Brink's novel to the screen making a statement along the way about what was wrong in South Africa under the brutal repression of those that dared to make a stand.The carnage one sees in the film is hard to take. Especially, since one occurrence is directed to innocent children who are trying to make a stand about education. At the time, the white establishment labeled communist all those that dared oppose the ruling class. It's ironic that after things got to be democratic, those same rebels didn't turn the country into a communist state.The story centers on a white teacher that suddenly awakens to what is happening around him. His involvement comes through his gardener, Gordon, who is a decent man. When the gardener's son is arrested, Gordon turns to Ben for help. That will mark the beginning of Ben's passive attitude toward apartheid. By trying to help, Ben will be a marked man, a traitor to his people, according to even his own family.Donald Sutherland makes an excellent Ben, the former football star and teacher. We watch him as he gets deeply involved in his quest for justice in a land where it was unknown. Zakes Mokae, an immensely talented actor of stage and screen, plays Stanley the man that serves as a link between the struggling faction and Ben. Jurgen Prochnow plays the sadistic Capt. Stolz conveying all the cruelty and arrogance of the man. Janet Suzman is Ben's wife, a woman who doesn't want to see any changes in her cushy life.The surprise of the film is the appearance of Marlon Brando in a small, but pivotal role of Ian McKenzie, a barrister that brings the case to a court of justice, but it's defeated by the system. Mr. Brando made a tremendous contribution to the film.Ms. Palcy's film is a reminder of the injustice perpetuated in South Africa under the apartheid rule.

The story of a schoolteacher (Southerland) who's black gardener's son "disappears" in 1970s South Africa, accused of activism. Then the gardner disappears too. Then an innocent black woman who is a friend disappears.With each incident, the comfortable family-oriented bourgois teacher becomes more involved in the awful injustices inflicted on black civilians, activists or just suspected activists. He first asks some friends in the government to help out and is treated with empty reassurances and pats on the back. Then he brings suit against the government's Special Action Squad (or whatever the death squad is called) for the gardener's death. The gardener was clearly tortured and then murdered under the supervision of the Chief Minister of Villainy (Jurgen Prochnow) and Southerland hires a lawyer who was disillusioned long ago (Marlon Brando).But Southerland pushes too far. His friends ignore him. He loses his job and his son is expelled from the school. His wife wants things the way they always have been -- nice compliant kaffirs who serve dinner when you tinkle the little bell, and sense of security. His wife leaves him, taking their adolescent daughter who feels the same way she does. Southerland's son, who seems to have inherited his Dad's ears, insists on staying with him and observes all the goings on. Susan Sarandon is a reporter who is sympathetic but has seen it all before. In the end, Southerland loses everything, but, as Sarandon tells him, despite his own helplessness, his son has learned a good deal and represents the next generation.The performances are all fine. Southerland is subdued and thoughtful in a role which calls for exactly those characteristics. Marlon Brando is also a standout, bringing to the part a kind of amused disdain for Southerland's naivete. Prochnow is properly villainous without being entirely unreasonable. He does his best with an Afrikaans accent -- nobody has ever trilled his r's so thoroughly -- but he may have been miscast because he looks like such a nice guy. I don't mean that the villain has to look like a scuzzbag, but that he should have an appearance and demeanor that projects villainy and what Prochnow projects is more like Carl Roger's "unconditional regard." But, beyond the incidents presented in this particular movie, I wonder what the function of such a story is. The first response of any sensitive viewer is undoubtedly going to be white guilt or black self pity. It's ironic because almost the entire population of viewers, regardless of race, color, or creed, will have had absolutely nothing to do with the events we see.Personally, we will be gripped by the exposition of such injustice -- such outright murder by the authorities -- and that's fine as far as it goes. Beyond that, the movie-makers have given us an educational documentary-style film, beginning with a naive complacent white guy, a lot like many of the rest of us, and guiding him through a tour of corrupt racism, along with the viewer. (How he could have remained so innocent without having lived in a cave isn't explained.) I wonder in the long run if movies like this (and "Z" and dozens of others) don't have counter-productive properties. We feel not only sympathy but anger. In the final shot -- and I do mean "shot" -- the movie seems to endorse the idea that violence is the only appropriate response to injustice. Why should such a notion be expected to do anything other than drive a deeper wedge between minorities and the dominant majority? Is murder really the only way out of inequity? If they kill us, is our only response to kill them too? A more object lesson might be that colonialism doesn't work for long, but a lot of viewers may not be able to get past the violence on screen. And anyway, colonialism never calls itself "colonialism." It's always "The Crusades," or "spreading civilization," or "protecting our own interests," or "preventing the spread of" (fill in the blank with your own noxious ideology).There's a semi-happy ending. Southerland's son will live to straighten things out. But it's a pale message and seems tacked on. Our amygdalas stand up and applaud at the end when Prochnow gets a bullet through his heart.Peace, brothers and sisters.